Yellowstone National Park, a symbol of America’s rich natural heritage, is now at the epicenter of a growing epidemic that could pose risks far beyond its borders. A mule deer buck found dead in October marks the first confirmed case of chronic wasting disease (CWD) within the park’s boundaries. This alarming development has raised concerns among scientists about the potential for this fatal disease to jump from wildlife to humans.

Known colloquially as “zombie deer disease” due to its debilitating symptoms, CWD has been surreptitiously spreading across North America. Its presence in Yellowstone – a region home to the most diverse array of large wild mammals in the continental US – is a significant turning point. “This case puts CWD on the radar of widespread attention in ways it wasn’t before – and that’s, ironically, a good thing,” explains Dr. Thomas Roffe, a veterinarian and former chief of animal health for the US Fish & Wildlife Service.

A Silent Killer Among the Herds

Caused by prions, abnormal pathogenic agents, CWD induces severe changes in the brains and nervous systems of affected animals. Infected deer, elk, moose, caribou, and reindeer exhibit drooling, lethargy, emaciation, stumbling, and a haunting “blank stare.” Despite its alarming spread, there are currently no known treatments or vaccines for this invariably fatal disease.

Years of Warnings Were Ignored

Dr. Roffe had long forewarned about the arrival of CWD in Yellowstone, urging both federal and state governments to adopt aggressive containment measures. And when we say that the Dr. has long warned about it, we mean over the last two decades. In fact, this isn’t the first outbreak of CWD in the region.

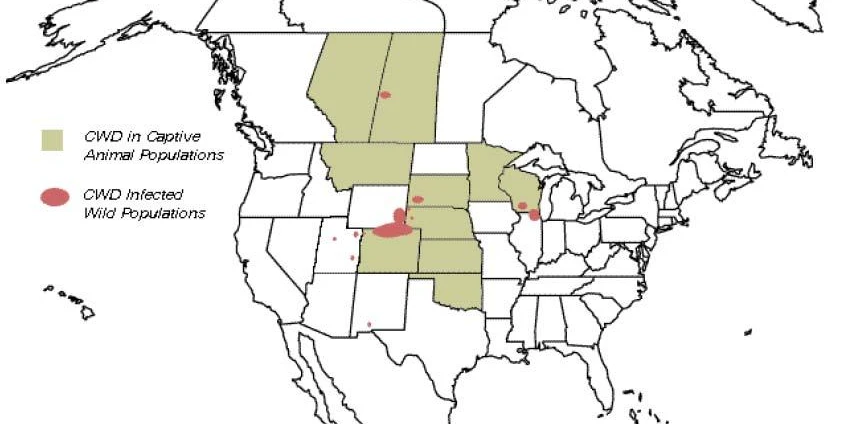

The map below shows the spread of CWD in 2004 – twenty years ago. The government chose not to take action then and is choosing to do little now.

Unfortunately, these calls for action were largely overlooked. “Those warnings went largely unheeded,” he laments, “and now the consequences will play out before the millions who visit the park each year.”

Yellowstone serves as a natural laboratory, allowing observers to witness firsthand the impact of CWD on an ecosystem teeming with biodiversity. The disease’s infiltration poses a severe threat to the park’s dynamic food chain, from hundreds of thousands of elk and deer to the predators and scavengers that depend on them.

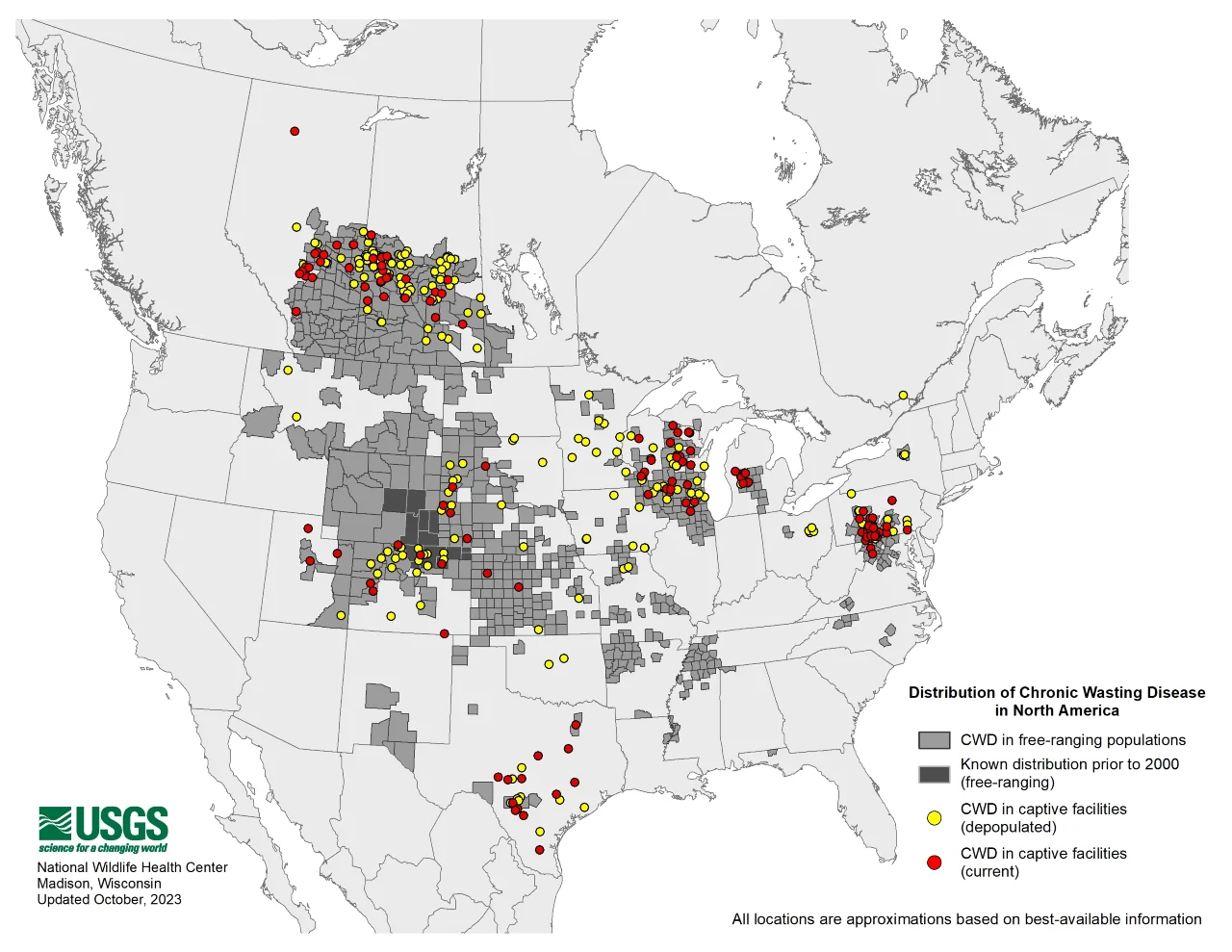

Below is a map, as of November 2023, highlighting the regions with verified cases of CWD in deer, elk and moose. You’ll notice the striking similarities between the map below and the one from twenty years earlier.

The Shadow of ‘Mad Cow’ and Future Fears

Drawing parallels to the ‘mad cow disease’ crisis, Dr. Michael Osterholm, an epidemiologist, describes CWD as a “slow-moving disaster.” His colleague, Dr. Cory Anderson, underscores the gravity of the situation, “We’re dealing with a disease that is invariably fatal, incurable and highly contagious.” The pathogen’s resilience, capable of surviving extreme conditions and resisting conventional eradication methods, adds to the gravity of the crisis.

The Threat of ‘Zombie Deer Disease’ Crossing Species

In the U.S. and Canada, the alarm over Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) is twofold. Not only does it impact prized big-game animals, but there’s also the looming fear that it could leap across species. The potential for deer, elk, and moose to transmit the disease to livestock, other mammals, birds, or even humans is a growing concern among epidemiologists. While no such “spillover” case has been reported yet, the absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence. This disease belongs to a group of fatal neurological disorders, including the notorious BSE, or “mad cow disease.”

“The BSE [mad cow] outbreak in Britain provided an example of how, overnight, things can get crazy when a spillover event happens from, say, livestock to people,” explains Dr. Cory Anderson. “We’re talking about the potential of something similar occurring. No one is saying that it’s definitely going to happen, but it’s important for people to be prepared.”

A Global Health Perspective

Dr. Raina Plowright, a disease ecologist at Cornell University, highlights that CWD should be seen in the context of dangerous zoonotic pathogens increasingly crossing species barriers. These outbreaks are often facilitated by human encroachment into wildlife habitats.

As hunting season commences in the U.S., the Centers for Disease Control and individual states strongly recommend testing harvested game animals for disease. They advise against consuming meat from cervids that appear sick.

Unseen Risks on the Dining Table

The Alliance for Public Wildlife estimated in 2019 that between 7,000 to 15,000 CWD-infected animals are unknowingly consumed by humans each year, a figure expected to rise by 20% annually. In Wisconsin, where game meat testing is voluntary, Anderson and Osterholm suggest that many thousands might have already consumed infected deer meat.

Rising Infection Rates Require Revising Strategies in Yellowstone

Wyoming, often used as a reference point for other states, has been rigorously collecting and testing tissue samples since 1997. Breanna Ball, from the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, shares that last year alone, the meat from 6,701 deer, elk, and moose was tested, with about 800 samples showing disease presence, indicating an uptick in infection rates.

According to the U.S. Geological Survey, CWD has now infiltrated 32 states and three Canadian provinces, marking its relentless spread across North America.

Following the confirmed case of CWD within Yellowstone, park authorities are rethinking their approach to monitor and manage the increasing number of sick animals. Dr. Thomas Roffe explains that the virulence of CWD is “density dependent,” with higher infection rates in areas where large numbers of animals congregate.

Controversy Over Artificial Feeding

A rather large concern for experts is the artificial feeding of wildlife. In Wyoming, nearly two dozen “feedgrounds” for elk are operated by state and federal governments, where over 20,000 animals receive alfalfa, en masse, during winter. This practice, however, is widely criticized by leading wildlife management organizations. “The science of what’s needed to help slow the spread of CWD is clear, and has been known for a long time,” Roffe emphasizes. “You don’t feed wildlife in the face of a growing disease pandemic.”

Role of Natural Predators & Wildlife Policies That Got In The Way

Studies suggest that predators, often seen as competitors by hunters, may actually be crucial allies in this battle against disease. Wolves, cougars, and bears have a natural ability to detect and prey on sick animals, effectively removing them from the population. Notably, these predators have so far shown immunity to the disease.

Wildlife conservationists point out a major policy contradiction in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, encompassing Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho. These states promote the liberal hunting of wolves and cougars for sport and livestock protection, a practice often unnecessary and potentially counterproductive in controlling CWD.

“We’re still at the front end of a scary disease event, and we don’t know where it’s headed,” says Roffe. The stakes are high not just for the Yellowstone ecosystem but also for Americans who value healthy wildlife. The spread of CWD presents a clear danger, with implications that stretch beyond the park’s borders, impacting wildlife management and public health.

More To Discover

- Texas A&M Researchers Explore Black Soldier Fly’s Potential in Tackling State’s Manure Issue

- South Korea’s Pivotal Move to Ban Eating Dogs: A Reflection of Changing Times and Attitudes

- Regional Differences Drive Distinct Motivations for Energy-Efficient Home Upgrades Across the U.S.

- Starbucks in Hot Water: Lawsuit Challenges Their ‘100% Ethical’ Coffee Claims

Conclusion

The emergence of ‘zombie deer disease’ in Yellowstone National Park is a stark reminder of the intricate balance between wildlife, ecosystems, and human activities. As the disease continues to spread, the role of human intervention – both as a potential contributor to the problem and as part of the solution – becomes increasingly evident. The park’s response, alongside broader wildlife management strategies, will be pivotal in determining the future of not only Yellowstone’s diverse wildlife but also the health and safety of humans potentially at risk from this evolving threat.