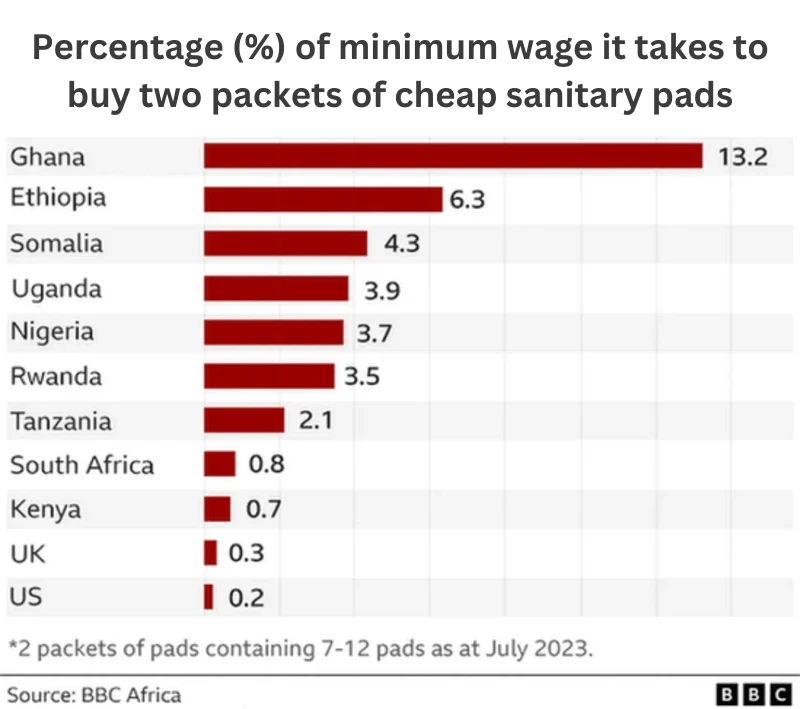

Picture this: women and girls across much of the developing world facing a monthly struggle due to the lack of access to menstrual products. It’s a deeply concerning issue that not only disrupts their daily lives but also hinders their educational and economic progress. Imagine missing school for at least a week every month, and the long-term consequences it has on one’s life. It’s a reality that many are forced to live with.

In the quest for more sustainable menstrual products, there’s been a shift away from traditional options often made from petrochemical-based hydrogels, which are harmful to both our bodies and the environment. Instead, the focus has turned to biomaterials. However, most of these alternatives rely on cellulose from wood, a resource in high demand for various industries, and not always readily accessible in regions where it’s needed the most.

Enter Alex Odundo, a visionary from Kenya. He’s found a unique solution that not only addresses this issue but also harnesses the power of nature.

Alex, together with collaborators in Manu Prakash’s lab at Stanford University, embarked on an incredible journey to create maxi pads from sisal, a hardy agave plant that thrives in semi-arid climates like his homeland.

Sisal might seem like an unlikely hero, often considered an invasive plant in rural Kenya. It’s typically used for livestock fencing and feedstock.

What makes sisal special is its resilience—it doesn’t need fertilizers, and its leaves can be harvested year-round over several years. Alex and his team developed an ingenious process to transform sisal leaves into soft, absorbent material.

Their method involves treating sisal leaves with a gentle solution of dilute peroxyformic acid (just 1 percent) to increase its porosity. Then, a wash in sodium hydroxide (4 percent) follows, with a final touch of spinning in a tabletop blender to enhance softness and porosity.

Now, let’s talk about how well it works. They tested their sisal fibers with a mixture of water and glycerol, mimicking the consistency of blood. The results were astonishing. Sisal proved to be just as absorbent as the cotton used in commercially available maxi pads. It even held its own compared to wood pulp and outperformed other biomaterials like hemp and flax. And here’s the kicker—their process is far less energy-intensive than the conventional methods that rely on high temperatures and pressures.

Beyond its efficacy, the environmental angle of their work is equally impressive. When considering the entire life cycle, including sisal cultivation, harvesting, manufacturing, and transportation, sisal cellulose microfiber production is on par with wood. It even outshines cotton in terms of both carbon footprint and water consumption. Much of the environmental impact comes from transportation, emphasizing the importance of local production.

But Alex Odundo’s dedication to sisal doesn’t stop at maxi pads.

For over a decade, at Olex Techno Enterprises in Kisumu, Kenya, he’s been crafting machines that turn sisal leaves into valuable rope. This not only benefits local farmers but also offers a source of income that’s up to ten times more profitable than selling sisal leaves.

In addition, Odundo designed a wood stove that burns materials like sawdust and rice husks, effectively addressing deforestation concerns. Simultaneously, it improves the respiratory health of women, who often endure the smoke from traditional cookfires. It’s a thoughtful innovation that takes into account the practical needs of the people who use it, a refreshing departure from prototypes developed without their input.

In essence, this partnership between Alex Odundo and Manu Prakash’s lab at Stanford embodies the spirit of “frugal science.” It’s about making science accessible to all, particularly in low-income rural communities where it’s needed most. By producing menstrual products within these communities, this initiative doesn’t just address a pressing humanitarian issue—it also champions sustainability and empowers local populations.

More To Discover

- World’s Oceans Hit New Temperature High, Sparking Climate Concerns

- The Future of Our Cities: Powered by… Toilet Water?

- Labor Crisis Sparks AI Boom on US Farms: Can They Save Our Food Supply?

- Silkworms Challenge Nylon and Kevlar in Environmental Showdown: Genetically Enhanced Caterpillar Set to Revolutionize Green Fabric Production

But let’s not forget the bigger picture. Period poverty is a global concern, affecting women in various ways. In many parts of the world, access to menstrual products remains limited. Even when options exist, they may not be affordable or practical. Often, cultural stigma and taboos surrounding menstruation further compound the problem. The result? Girls missing school, women missing work, and a cycle of inequality that’s hard to break.

As we strive for a more sustainable and equitable world, initiatives like these remind us of the power of innovation, collaboration, and empathy. This holistic approach, blending science, entrepreneurship, and social responsibility, has the potential to uplift communities and inspire positive change. It’s a testament to the human spirit and our capacity to make a difference, one sisal maxi pad at a time.