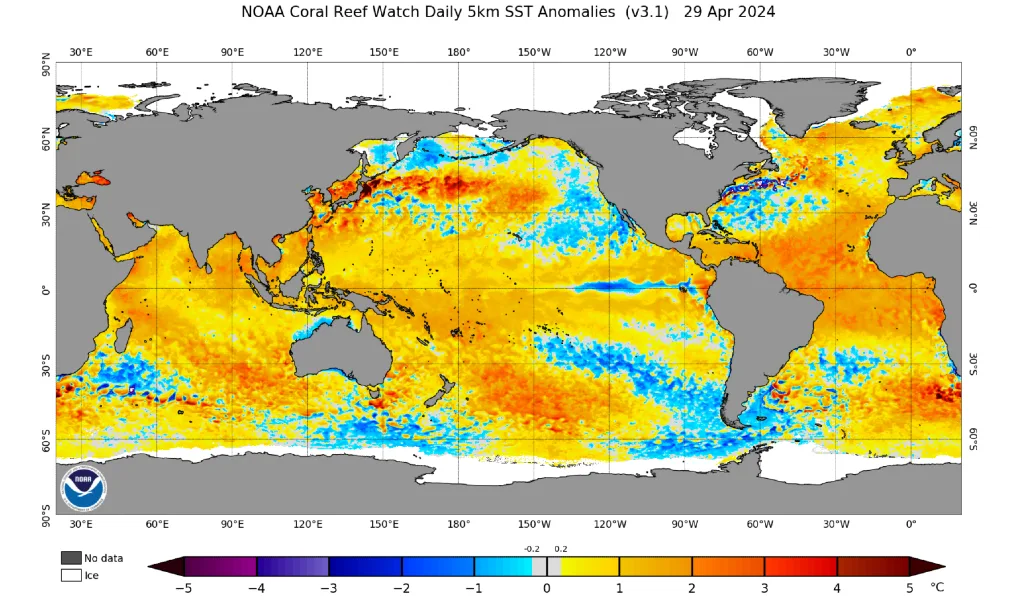

Ocean heatwaves are now affecting nearly 30 percent of the world’s oceans—an area as large as North America, Asia, Europe, and Africa combined. Recent spikes in ocean temperatures have led to widespread die-offs of various marine species, devastating millions of corals, fish, mammals, birds, and plants. This ecological catastrophe is also impacting marine scientists emotionally, as they witness the destruction of ecosystems they’ve dedicated their careers to studying.

Jennifer Lavers, a researcher with the nonprofit Adrift Lab, expressed her distress, “We talk a lot about eco grief, that sense of being overwhelmed and feeling loss.” Lavers has observed firsthand how thousands of seabirds have starved to death off the coast of Western Australia due to these heatwaves.

Although the current extreme heat in her region is subsiding, the global situation remains dire. Nearly 30 percent of the world’s oceans are currently experiencing marine heatwave conditions. Lavers noted that while the gradual warming of oceans has been well-documented, recent studies indicate that sudden spikes in temperature are causing the most severe damage to marine ecosystems.

The increasing frequency of these extreme heat events has led to more mass die-offs and has discouraged many dedicated scientists from the field. Lavers shared her frustrations, “Incredibly skilled, talented, qualified, very passionate people are leaving because no matter what they say, what they do, how many papers they publish… It doesn’t matter.”

The marine life they aim to protect continues to decline, leaving researchers like Lavers in a grim position. I have to literally say to people that my job is to describe the extinction of a species,” she stated.

In recent years, as the ocean off the west coast of Australia endured prolonged periods of high temperatures, Lavers and her team have documented the increasing numbers of emaciated seabirds, many of which had ingested large amounts of plastic, washing up on shores.

Lavers also touched on the emotional toll this work takes on new researchers, “I’m supposed to go to work each day and inspire the next generation of young scientists. They start off excited, thinking they’ve landed their dream job. But within days, they’re in tears as they see the impact of pollution on these birds.”

The Hidden, Yet Widespread Impacts of Ocean Warming

Ben Noll, a climate scientist at New Zealand’s National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research, recently found that 78 percent of the world’s non-ice covered oceans are experiencing marine heatwave conditions. “The situation is dire,” Noll stated, emphasizing the critical and extreme nature of the recent warming. These effects are mostly unseen by the public and only observable to those who work closely with the ocean, such as researchers and divers.

Noll highlighted the growing normalization of these extreme events, “These events are becoming normalized.” In New Zealand, public awareness of marine heatwaves increased when they led to the hottest month on record in January 2018 and again in 2023 when they contributed to devastating storms. However, the term ‘marine heat wave’ is losing its impact as these events become more frequent.

The consequences of ocean heatwaves extend far beyond temperature anomalies. They’re also a crucial factor in predicting the severity of the upcoming hurricane season in the tropical North Atlantic. Research suggests that ocean warming doubles the likelihood of intense tropical storms in the Southeastern United States and the Caribbean.

Recent studies also link ocean heatwaves to increasing occurrences of dangerous algal blooms. These blooms, which produce toxins, pose significant risks to fish, birds, and marine mammals, and can lead to the expansion of dead zones in coastal areas.

Extreme Ocean Heat: Exceeding Predictions and Causing Mega-Extinctions

Current ocean temperatures in some parts of the Atlantic are so high they’re considered off the charts. Lavers remarked on the unexpected scale of the warming, “It was so extreme that it was considered an unlikely model prediction, yet here we are.” This rapid and intense warming is alarming climatologists and significantly impacting marine species.

The impact on emperor penguins in Antarctica exemplifies this issue. A recent study from the British Antarctic Survey noted significant chick losses among emperor penguin colonies as sea ice reached record lows. These extremes are pushing marine ecosystems beyond their thresholds, leading to widespread die-offs.

In Australia, the majority of seabirds found dead or dying on beaches were breeding adults, which poses a significant threat to the future of these populations.

Curtis Deutsch, an oceanographer at Princeton University, emphasized the importance of addressing extreme warming events, “An extreme event typically only lasts a short time, but that doesn’t always mean that the system comes back from it.”

More To Discover

- Why Mass Tree Planting Might Not Be the Green Savior We Hoped

- Self-Growing Beef Cells Promise Cheaper, Sustainable Meat

- Vanuatu Stops Chinese Logging Firm Amid Theft Claims and Workers In Chinese Military Uniforms

- Electric Scooter Concept Aims to Overcome EV Challenges with Automated Battery Swap System

Despite the challenges, Lavers remains committed to her work, “Even when you’re crying, and you feel like there’s no hope, our job is to give a voice to the voiceless. I will fight on to the very end to give them the voice they so desperately deserve.” This sentiment underscores the critical and urgent nature of addressing global warming and ocean heatwaves.

Source: Global Change Biology