Cheese, a beloved dairy product enjoyed worldwide, has come a long way in terms of its production methods. While most cheese today is churned out in large-scale factories, it hasn’t always been this way. For centuries, cheese making was a craft practiced by individual families and farms, with small batches lovingly crafted and sold locally.

So, when and why did cheese making transition to an industrial scale? In this article, we will delve into the fascinating journey of cheese making, exploring the stages that led to the emergence of large-scale factory production.

To comprehend the transformation of cheese making, we must first examine three key stages:

- the development of the infrastructure necessary for cheese factories,

- the inception of the earliest cheese factories,

- the eventual full-scale industrialization of cheese production within these factories.

The advancements made by Harding and his contemporaries set the stage for the birth of cheese factories. With improved equipment and techniques, small-scale cooperative models emerged, wherein farmers from multiple farms pooled their milk resources to supply larger-scale factories. While Switzerland witnessed the establishment of one such factory in 1815, its lifespan was short-lived, leading to its eventual closure.

In the next section, we will explore the resurgence of cheese factories and the complete industrialization of cheese making, marking a transformative era for the cheese industry.

A More Industrialized Era: The Impact of the American Civil War and Cross-Atlantic Exchange

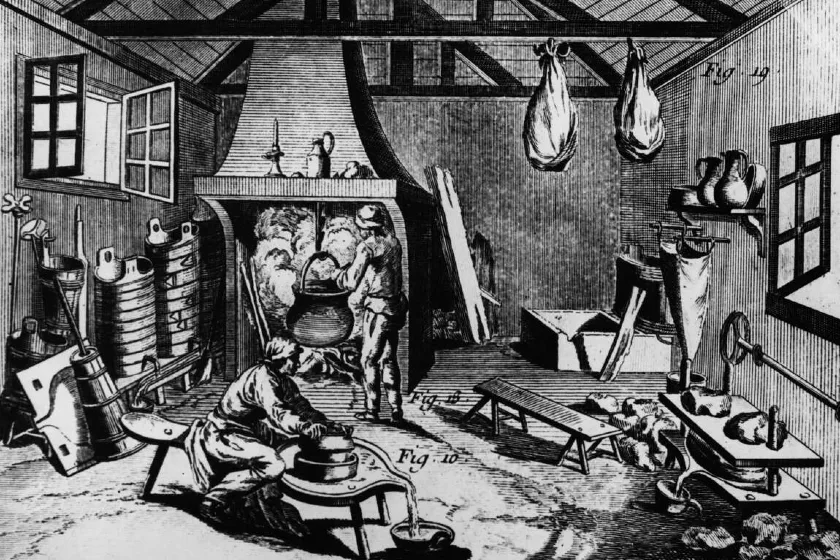

Historically, cheese making predominantly took place on farms, rooted in local communities. The first step towards industrialization occurred on these farms, particularly in the 17th century. Cheese making experienced a surge in popularity in both England and the Netherlands, and cheese makers sought ways to reach a broader market. This pursuit led to significant changes in cheese production techniques, including advancements that enhanced the longevity and transportability of cheeses. Notably, iconic cheeses like Gouda and Cheddar emerged during this period.

As the 19th century dawned, the Industrial Revolution was in full swing, providing farm cheese makers—often dairy women—with new equipment that facilitated increased cheese production.

This, in turn, led to the expansion of dairy herds and the construction of dedicated cheese houses on farms.

Additionally, farmers began selling their milk to specialized cheese dairies instead of making cheese themselves, further driving the shift towards centralized production and creating the nation’s first niche cheese markets.

Scientific understanding played a crucial role in the mid-19th century as scientists and cheese makers, particularly in England, delved into the intricacies of cheese making. Until then, cheese making had been largely regarded as an art. Mastering the craft required years of intuition and experience. However, with the emergence of scientific inquiry, the guesswork began to dissipate.

Through deliberate experiments and meticulous record-keeping, scientists unraveled the mysteries of cheese making. Their discoveries simplified the process, allowing for consistent results in terms of flavor and texture. These findings were shared through scientific journals, disseminating valuable knowledge that empowered cheese makers to improve their own practices. The scientists also played an educational role, enlightening cheese makers about these new insights.

One notable figure in this movement was Joseph Harding, often referred to as the father of Cheddar. Settling into dairy farming and Cheddar-making in 1851 at Vale Court Farm, situated slightly north of the traditional Cheddar-making region, Harding was determined to unlock the secrets of Cheddar production. He conducted experiments, testing different procedures and incorporating best practices from other cheese makers.

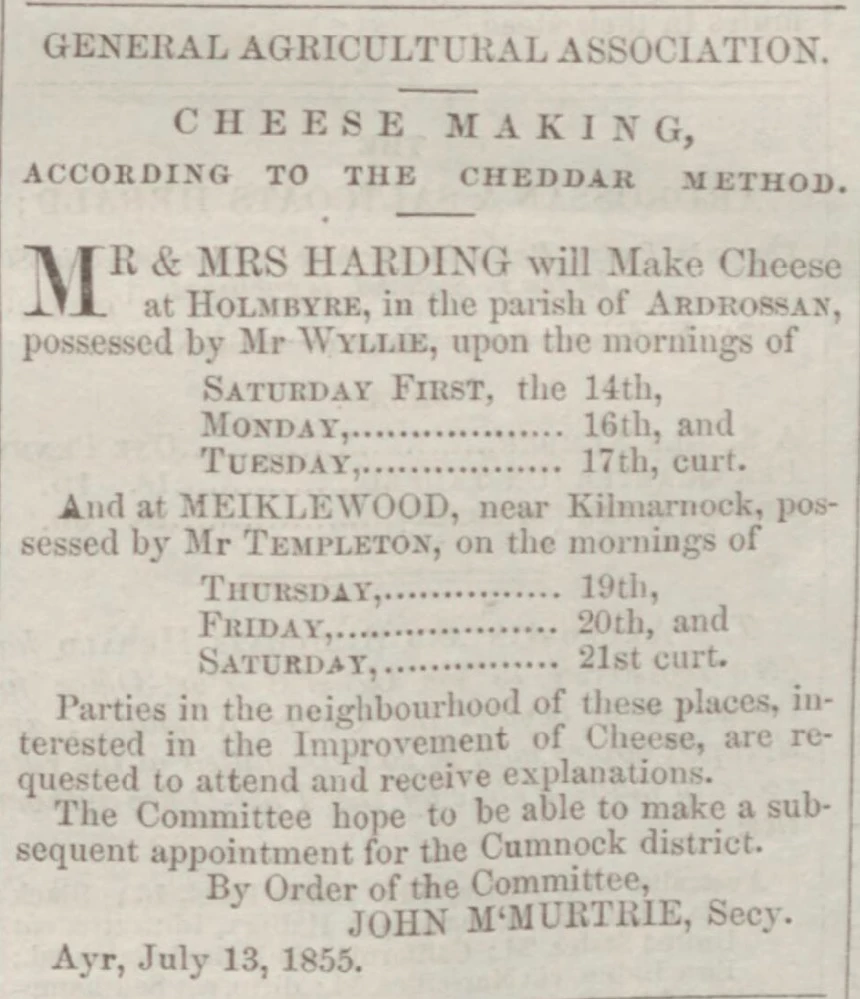

In July 1855, a short article in the Ardrossan Herald states “The Ayrshire Agricultural Association are practically showing they desire to advance the manufacture of cheese in the county. They have brought Mr and Mrs Harding from Somersetshire, for the purpose of giving instructions in the Cheddar method of cheese making – a method, which according to the report published sometime ago by the deputation who had been sent to England to examine into the method, was considered much superior to the Ayrshire. They are likely to visit this district soon.”

Harding’s cheese classes proven popular and by August, articles began appearing touting his education and attendance.

In July 1859 a column called “The Farm” ran a piece on cheese-making which ran in many newspapers throughout the country. A report by Mr. Fulton of Temple Maryhill near Glasgow said that “it is clearly ascertained that the quality of the cheese is determined almost entirely by the mode of manufacture. … ‘Whilst in Ayrshire,’ writes Mr. Harding, ‘we made cheese in almost every part of the country . . . and the cheese was uniform in texture, quality and Flavour; if there was any sensible difference, our impression was that the best article was made at Corwar.‘” He followed that with a detailed tutorial.

Recognizing the improvement in his own cheese, Harding shared his knowledge with others through an article published in 1860 in the Journal of the Royal Agricultural Society of England. In this article, he detailed his innovation of scalding the Cheddar curd before milling, resulting in a finer texture of cheese.

The establishment of enduring cheese factories began to take shape in 1851, with Jesse Williams leading the way in Oneida County, New York. Williams, along with his son George, convinced their neighbors to contribute their milk in exchange for a share of the cheese profits.

In May of that year, the Williams Cheese Factory commenced production, churning out over 100,000 pounds (45,000 kg) of stirred-curd Cheddar cheese during its first season. This output was five times more than what a sizable farmstead operation could achieve at the time.

The advantages of increased efficiency, cost-effective bulk supplies, and enhanced cheese uniformity made the Williams’ experiment an immediate success. As a direct result, new factories began to emerge throughout the New York countryside, representing a crucial shift towards a larger-scale cheese-making approach.

While these early factories were not industrial in the modern sense, they were certainly factories nonetheless. They still adhered to traditional cheese-making methods but operated on a larger scale than individual farms. The cheese produced in these local factories exhibited greater consistency compared to the variations found among cheeses produced on different farms.

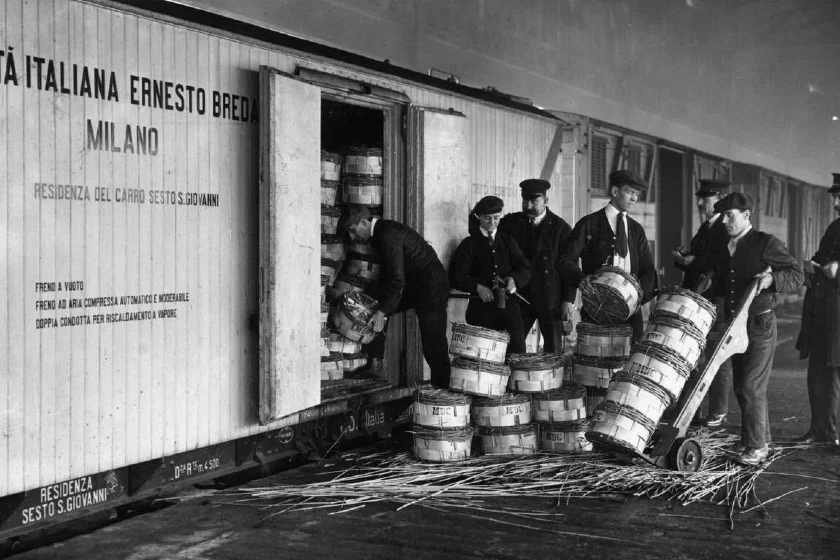

These small-scale factories quickly proliferated across America during the following decade, even exporting their cheese overseas, particularly to Britain. A parallel trend emerged in the late 1850s, as similar cheese factories started to develop in other regions around the world. Notably, France witnessed the scaling up of Camembert production in Normandy to meet the growing market demand.

However, in France, cheese-making remained largely localized, resulting in a diverse array of cheeses that the country is renowned for today.

While these early cheese factories represented an evolution from farm-based operations, they still had a way to go before resembling the industrialized factories of the present day. However, this transformation occurred at an accelerated pace. The catalyst for further development came in the form of the American Civil War, which commenced in 1861.

Many workers from the northern cheese factories enlisted in the Union Army, leaving factory owners faced with the challenge of maintaining cheese production with reduced labor. This necessity led to technological advancements as a means to compensate for the labor shortage.

Of course, this meant that many farms ceased their own cheese production, redirecting their milk supply to the factories. With men away at war, women shouldered the responsibility of farm management, leaving them with less time for cheese making. Consequently, cheese production on individual farms dwindled, and the focus shifted to centralized factory production.

The outbreak of the American Civil War amplified the attractiveness of the English market. English merchants paid for goods in gold currency rather than the increasingly devalued American paper currency.

This led to a surge in new cheese factories across the United States, with exports to England skyrocketing from 5 million pounds (2.3 million kg) in 1859 to a staggering 50 million pounds (23 million kg) in 1863. The demand for American cheese was booming.

Around the mid-1860s, while cheese factories were thriving in America, significant advances in scientific understanding of cheese making were occurring in England. The post-Civil War period became a turning point as these two forces finally converged, thanks to Xerxes Willard, a representative of the American Dairyman’s Association.

In 1866, Willard embarked on a journey to England to study dairies and investigate their cheese-making practices, seeking any insights that American factories could adopt and adapt.

The encounter between scientific knowledge and the burgeoning American cheese factory industry would lay the foundation for the next phase of industrialization, propelling the cheese-making landscape into new realms of efficiency and standardization.

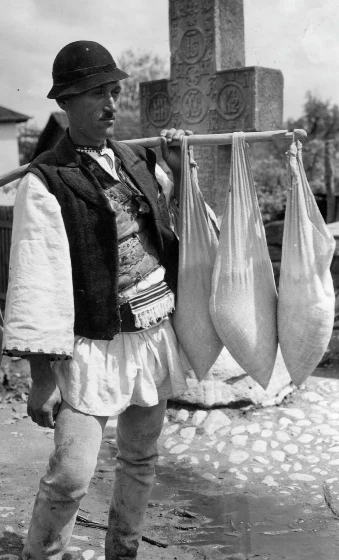

In the video below, a Romanian cheesemaker continues to use the centuries old techniques to make cheese on his family farm. It’s a long video, but it demonstrates much of the traditional processes used over a century ago.

Play Video

The Rise of Industrial Cheese: Transforming Cheese-Making Practices

Joseph Harding, a prominent figure in the quest to understand cheese making, played a pivotal role in further propelling the industrialization of cheese factories. Harding implemented a scientific approach that involved precise schedules for time, temperature, and acidity at various stages of the cheese-making process.

This newfound control over cheese quality and consistency caught the attention of Xerxes Willard, who brought Harding’s techniques back to America. Willard concluded that American dairymen could benefit greatly from the Cheddar-making process. Willard’s insights were eventually published in Willard’s Practical Dairy Husbandry, a comprehensive resource on dairying and cheese making.

Harding’s innovations not only aimed to improve Cheddar production, but also inadvertently paved the way for its widespread replication. The dissemination of knowledge through journals made it accessible to cheese makers across regions. The improved technology introduced by Harding facilitated the rise of American Cheddar-cheese factories, granting them a significant competitive advantage by enabling larger-scale operations and reducing production costs.

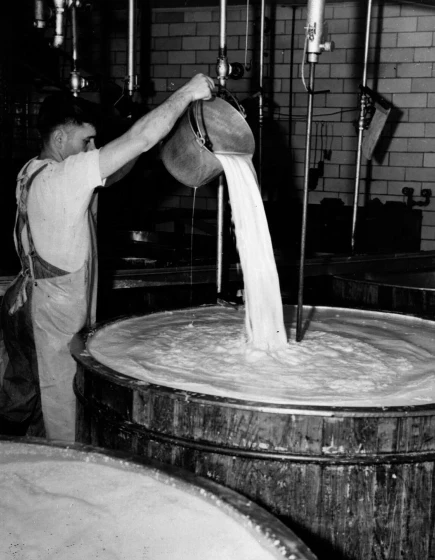

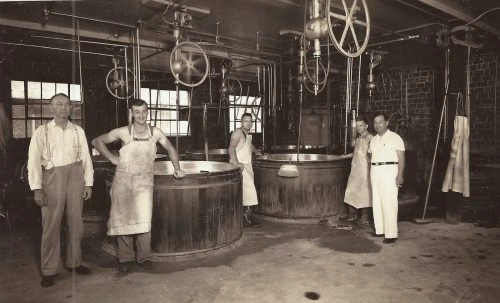

As scientific understanding advanced and cheese-making operations grew in scale, more technological developments emerged within cheese factories. Traditional knowledge and manual processes gradually gave way to reliance on machinery.

Technological advancements included the introduction of steam boilers for milk heating and the “gang-press,” enabling the simultaneous pressing of multiple cheeses. The expansion of cheese factories necessitated larger equipment to process greater quantities of milk and produce more cheese.

These advancements quickly spread to other countries, eager to capitalize on the industrialization of cheese making.

The Netherlands, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand established cheese factories to supply export markets, particularly the British market, where they directly competed with American-made cheese. In Britain, the shift toward industrialization was slow and primarily driven by the decline of local cheese making in favor of imported varieties, notably Cheddar.

While American-style factories initially appeared in Derbyshire, England, in the early 1870s, their success was short-lived. Several factories switched to handling liquid milk or butter instead of cheese, aligning with the trend of focusing on liquid milk transportation via railways to meet the growing markets.

The availability of imported cheeses, often cheaper and more consistent than local products, further contributed to the decline of British cheese producers.

It was not until the 1930s that English cheese making caught up with the industrialization observed in other countries. In France, cheese makers formed syndicates and associations to protect their regional cheeses from being overshadowed by larger external producers.

These efforts resulted in the establishment of the Appellation d’origine contrôlée, a system that safeguards specific cheese names, production areas, and techniques, thereby preserving the quality and local characteristics of French cheeses. In the mid-20th century, France also embraced technological advancements in cheese making, which led to a decline in artisanal cheese makers during the 1950s.

The Journey from Farm to Factory

And so, the journey of cheese making transitioned from a practice carried out on individual farms to small-scale co-operatives, and ultimately to the colossal industrial factories capable of producing thousands of cheeses per day. The United States played a pioneering role in each stage of this development, with other countries gradually following suit at their own pace. Today, the majority of cheese production is factory-made, characterized by consistency and reliability.

However, amidst this transformation, small artisanal cheese makers have continued to thrive, employing traditional methods to craft cheeses with unique flavors and complexities.

Similarly, there are still small cheese factories dedicated to producing traditional styles of cheese.

The choice between mass-produced, factory-made cheese and small-scale artisanal varieties depends on individual preferences.

While factory-made cheese offers consistency and convenience for everyday use, the allure of local and homemade cheeses, with their intricate flavors, often takes center stage on cheese boards, particularly when aiming to impress guests.

So, where do you stand in this cheese conundrum? Are you a fan of mass-produced cheese, or do you prefer the diversity and intricacies of artisanal creations?

Perhaps you even make your own cheese. Share your thoughts in the comments below by getting yourself a Dakoa membership while it’s still free.

As for me, I find myself gravitating towards mass-produced cheese for cooking and daily consumption, where flavor takes a back seat.

More To Discover

- 8 Alarming Trends in Corporate Control of Our Food Supply

- Chewing On the Key Challenges in Our Current Food System

- Nestlé Resists Investor Pressure to Reduce Unhealthy Ingredients in Its Products

- FTC Report: Grocery Stores Boosting Profits, Driving Up Food Prices While Falsely Blaming Inflation, Supply

However, when it comes to special occasions and cheese boards, I delight in savoring the complex flavors of local and homemade cheeses, leaving a lasting impression on my guests.

400 Years of Cheese Craft In 8 Photos