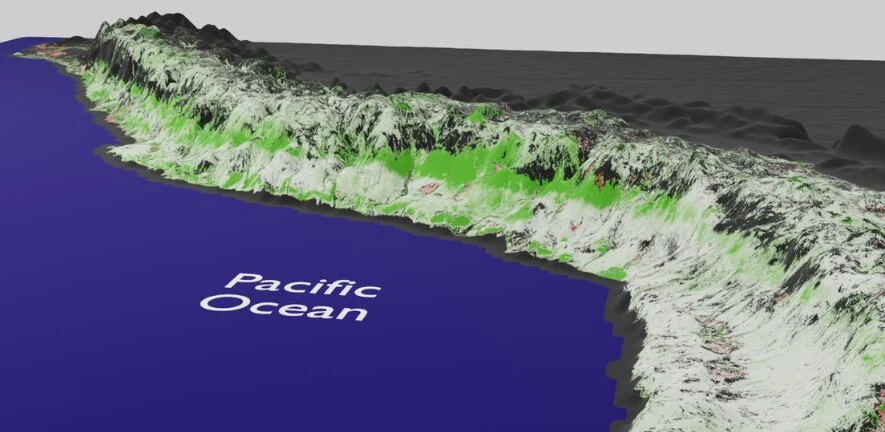

Satellite observations spanning two decades indicate that a long stretch of desert coast, starting from northern Peru and reaching into Chile, is becoming increasingly verdant. However, this shift may not be the positive change it seems.

Cambridge University’s mathematician, Hugo Lepage, compares the situation to “the canary in the mine,” implying a significant warning.

Dotting this 2,800-kilometer arid coastline are patches of special vegetation known as lomas. These lomas owe their existence to fog from the sea, as the region itself receives a meager annual rainfall between 3 and 13 mm. In fact, some years witness no rainfall whatsoever.

Several unique species, including wild tomatoes, the rare Andean Condor, and the popular air plants (Tillandsia), reside in these green pockets amidst the desert.

The lomas’ existence tends to oscillate with climate patterns, sometimes vanishing for nearly a decade. Yet, rainy seasons brought on by El Niño can also usher in extraordinary blooms.

Recent satellite data shows the lomas are expanding. While this may seem beneficial for the local endangered wildlife, it’s indicative of potential challenges elsewhere.

The greening effect isn’t just natural; human activities are playing a role. Farmlands, powered by irrigation, are spreading, contributing to the region’s increased vegetation. But this shift impacts the lomas directly, and some other regions are even witnessing the opposite effect – browning.

Cambridge University geographer, Eustace Barnes, highlights the importance of the Pacific slope: “It furnishes water for two-thirds of Peru and is a significant source of the nation’s food. The sudden shifts in vegetation, water levels, and ecosystems are bound to influence water and agricultural strategies.

When Lepage and his team delved deeper into their findings, they made some intriguing observations. “As we move southward, the elevation rises. This is unusual because we’d typically expect a decrease in surface temperatures when heading south and when moving to higher altitudes,” notes Barnes.

The most unexpected discovery was the most intense greening in historically parched zones. Lepage remarked on the unexpected correlation between the greening strip’s location and the associated climate zones.

Although it remains uncertain whether this greening trend is a result of a longer regional climate cycle or not, the observed patterns seem consistent with changes in rainfall patterns influenced by global CO2 concentrations over these two decades.

Decoding the link between the greening and land temperatures presents complexities, meriting further research.

Lepage leaves with a note of caution: “While we can’t halt such expansive shifts, being aware allows for more informed future planning.”

Ripple Effects: Beyond the Greening Coastline

The greening of Peru’s coastline isn’t an isolated phenomenon. The effects ripple through the ecosystem, influencing both local and distant habitats.

For starters, the increase in vegetation can attract new species to the area, potentially pushing out endemic species that have adapted to the traditionally arid environment. With the altered vegetation also comes changes in the local fauna. The endangered Andean Condor, which relies on certain native plants for food, may find its diet disrupted.

Beyond that, the sudden boost in vegetation can alter the water table. As plants use and store water differently, this can impact nearby rivers and streams, possibly affecting downstream areas that rely on these freshwater sources.

There’s also an economic impact to consider.

The region’s agriculture, which is intricately tied to the land and its resources, may experience shifts in crop yields, challenging farmers and the communities that depend on them. Such rapid environmental changes could also affect tourism, with potential shifts in local attractions and natural beauty spots.

What Can Be Done? Strategies for a Changing Environment

Addressing the rapid greening of Peru’s coastline requires a multipronged approach. Some of which local organizations and global charities have already started.

Conservation Efforts

Establishing protected zones can help preserve areas of significant ecological importance. This would prevent further human intervention, allowing the ecosystems to evolve naturally.

Research and Monitoring

Continuous monitoring using satellite data is crucial. This will allow scientists to track and predict changes, enabling proactive measures rather than reactive ones.

Water Management

Given the potential shifts in the water table, implementing advanced water management systems can help ensure that freshwater sources are not depleted. This includes the construction of sustainable irrigation systems for agriculture that are adaptable to changing environmental conditions.

Public Awareness and Education

Conducting workshops and training sessions for local farmers and communities can help them adapt to changing agricultural conditions. They can be introduced to alternative farming techniques and crops more suited to the evolving climate.

Support for Local Biodiversity

Initiatives to protect and, if needed, relocate endangered species can be vital. This ensures that the region's unique fauna and flora are not lost due to environmental changes.

More To Discover

- What Happens When There’s Less Wind To Power Our Turbines? Illinois’ Is Dealing With That Now.

- Court Halts Dicamba Use, Citing Unlawful EPA Approval

- Microplastics Are Basically Everywhere: Meat, Water, Produce, Packaging, Seafood And More. But Can They Really Hurt Us?

- The Groundbreaking Shutdown of the Original Nuclear Reactor Will Unlock More Future Fusion Insights

Collaboration

Engaging with international environmental organizations can bring in resources, expertise, and best practices from other regions experiencing similar challenges. This shared knowledge can be invaluable in crafting localized solutions for Peru's coastline.

By leveraging these potential solutions, it may be possible to mitigate the impacts of the changing environment and ensure that both the natural ecosystems and human communities can thrive. Of course, that will likely take a partnership between government (politics) and corporations and that typically ends in mostly greenwashing and lobbying.