In what can only be described as nature’s own plot twist, the San Joaquin Valley, a crucial artery in America’s agricultural heartland, bore witness to a phenomenal reemergence. Known for its parched landscapes and the pivotal role it plays in feeding the nation, this Californian expanse is typically associated more with drought than with deluge. Fresno, a central node in this vast agricultural network, averages a mere 10 inches of rainfall annually, a figure that can plummet to as low as 3 inches in lean years, according to the National Weather Service.

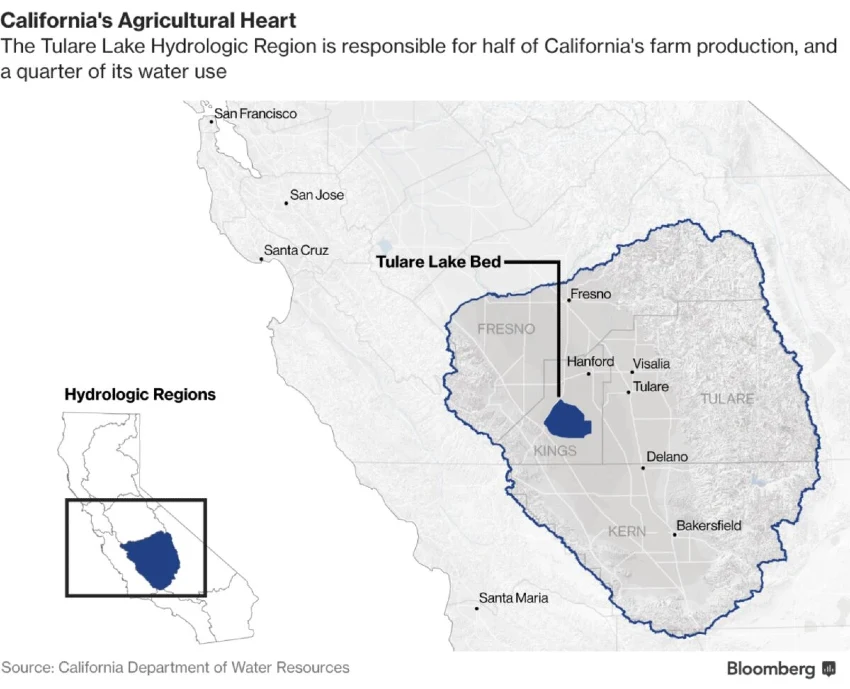

Yet, defying the arid reality of the present day, the San Joaquin Valley was once home to Tulare Lake, an expansive body of fresh water that stretched over 100 miles in length and 30 miles in breadth, making it the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi River until its disappearance some 130 years ago. And the second largest by surface area in the United States, or roughly four times the size of Lake Tahoe.

“It’s really difficult to imagine that now,” muses Vivian Underhill, who delved into the lake’s history and resurgence during their tenure as a postdoctoral research fellow at Northeastern University’s Social Science and Environmental Health Research Institute.

Underhill’s research, conducted while at Northeastern, shines a spotlight on the lake’s unexpected return in 2023, following a series of atmospheric rivers that drenched California. This event not only resurrected Tulare Lake from the annals of history but also cast a spotlight on its impact on indigenous communities, wildlife, and the agricultural workforce of the San Joaquin Valley.

Imagine a time when steamships plied the waters of this vast lake, ferrying agricultural supplies from Bakersfield to Fresno and onwards to San Francisco, covering nearly 300 miles. Such was the abundance of water in the region, a stark contrast to the irrigated landscape we see today, largely a result of human intervention.

“Pa’ashi,” as Tulare Lake was known to the indigenous Tachi Yokut tribe, depended primarily on the snowmelt from the Sierra Nevada mountains for its sustenance, rather than rainfall. With no natural outlet within the valley, the water pooled to form the expansive lake that Underhill describes.

Where Did The Water Go?

The transformation of Fresno from a lakeside town in the 1800s to its current state is a testament to the dramatic changes wrought over the centuries. Reports of driftwood lodged in the trees of downtown Fresno following floods in the era paint a vivid picture of the lake’s historical might and reach.

But where did all the water go? The lake’s decline began in the late 1850s and early 1860s, propelled by California’s push to transition public—and historically indigenous—lands into private ownership, effectively sidelining indigenous land claims.

The state embarked on a “reclamation” initiative aimed at converting inundated or desert lands into arable farmland, incentivizing white settlers to undertake the draining of Tulare Lake in exchange for land ownership. This process marked the onset of a deeply settled colonial project that saw the first complete disappearance of the lake around 1890, its waters diverted to irrigate the surrounding arid lands.

Fast-forward to 2023, and Tulare Lake—Pa’ashi—made an astonishing comeback, spurred by an extraordinary combination of heavy snowfall in the winter and torrential rains in the spring.

“California just got inundated with snow in the winter and then rain in the spring,” Underhill recounts, highlighting the cyclical forces of nature that brought this ancient lake back to life, if only temporarily, filling the depression where Tulare Lake once sat and reminding us of the ever-changing dynamics between human intervention and the natural world.

The Lake Is Back

As Tulare Lake reclaims its place in the San Joaquin Valley, its resurgence is a multifaceted phenomenon, marked not only by environmental renewal but also by deep-rooted cultural significance and socio-economic challenges.

Vivian Underhill emphasizes the historical recurrence of the lake’s appearance, noting, “It happened in the ’80s, it happened once in the ’60s, a couple of times in the ’30s.” This cyclical nature of the lake’s return underscores the dynamic interplay between natural forces and human interventions that have shaped the valley’s landscape over centuries.

The revival of Tulare Lake brings with it a stirring reawakening of wildlife, reminiscent of a time when, as Underhill recounts, “People talk about there being so many wetland birds,” that their collective takeoff would resonate “like a giant clap that resounded across the landscape.”

Today, less than a year after its return, the lake has become a sanctuary for “birds of all kinds—pelicans, hawks, waterbirds,” signaling a remarkable recovery of avian diversity. Moreover, the Tachi Yokuts have observed “burrowing owls nesting around the shore,” a sight that speaks to the resilience and adaptability of vulnerable species in the face of changing habitats.

The environmental benefits of the lake’s resurgence extend beyond biodiversity; the cooling breezes emanating from Tulare Lake can lower temperatures significantly, providing natural relief from the intense heat typical of San Joaquin Valley summers.

However, the human dimension of the lake’s return paints a more complex picture. For the Tachi Yokuts, the resurgence of Tulare Lake is imbued with profound spiritual and cultural resonance. “The return of the lake has been just an incredibly powerful and spiritual experience,” Underhill explains, highlighting the tribe’s deep connection to the land and the water.

The reemergence of the lake has enabled the Tachi Yokuts to “practice their traditional hunting and fishing practices again,” reconnecting with their ancestral heritage in a tangible and meaningful way.

Conversely, the agricultural community, which has long shaped the landscape of the Central Valley, faces mixed fortunes. Growers, who have developed “a complicated system of flood prevention,” find some of their efforts successful in protecting farmland, particularly in areas that coincide with the historic lakebed.

Yet, these protective measures have inadvertently exacerbated the plight of farmworkers, many of whom find themselves displaced by the encroaching waters. These individuals, often marginalized and linguistically isolated, bear the disproportionate burden of the lake’s resurgence, with many “experiencing the most personal, place-based impact in terms of having their housing flooded [or] losing their homes entirely.”

It Took 130 Years And The Media Called It ‘Flooding’

The reemergence of Tulare Lake in California’s San Joaquin Valley has sparked a narrative far richer than the headlines of disaster might suggest. Vivian Underhill, reflecting on the broader discourse surrounding the lake’s return, observes, “Most of the news coverage about this time talked about it as catastrophic flooding.”

However, Underhill is keen to balance this narrative by acknowledging the dual nature of the event: “And I don’t want to disregard the personal and property losses that people experienced, but what was not talked about so much is that it wasn’t only an experience of loss, it was also an experience of resurgence.”

This resurgence, marked by the return of native wildlife and the rejuvenation of cultural practices by the Tachi Yokuts, paints a picture of rebirth amidst adversity. Yet, this rebirth is under threat, as efforts to drain the lake have commenced once again. Underhill projects a temporary existence for the newly reformed lake, estimating it could persist “for about two more years—although new atmospheric river events over California this year could complicate that prediction.”

The conversation around Tulare Lake’s future is intrinsically tied to broader environmental considerations, with Underhill pointing out the role of climate change in increasing the frequency of significant flooding events. She suggests a reevaluation of the relationship between human management and natural water bodies: “At a certain point, I think it would behoove the state of California to realize that Tulare Lake wants to remain. And in fact, there’s a lot of economic benefit that could be gained from letting it remain.”

Underhill’s perspective invites a reflection on the impermanence of human alterations to the landscape, emphasizing that “this landscape has always been one of lakes and wetlands, and our current irrigated agriculture is just a century-long blip in this larger geologic history.”

More To Discover

This realization brings to light the transient nature of human endeavors when faced with the enduring rhythms of the natural world. “This was not actually a flood. This is a lake returning,” Underhill concludes, challenging us to reconsider our understanding of natural versus human-made changes to our environment.

The story of Tulare Lake, from its historical expanse to its contemporary resurrection, is more than California’s present-day Brigadoon, it’s a reminder of the unstable balance between human activity and the natural ecosystems that sustain us. As we navigate the challenges posed by climate change and ecological preservation, the lake’s return offers a unique opportunity to reimagine our relationship with the land and water that define our world.