In an unexpected twist, trees—typically hailed as environmental saviors—are now seen as contributors to climate change across vast swaths of the Great Plains, from the Dakotas to Oklahoma. Contrary to global trends where trees combat carbon emissions, here they exacerbate ecological issues, challenging the balance between forestry and grassland preservation.

The Surprising Impact of Trees in Grasslands

Eastern red cedars, once confined to small patches, are now dominant across many grasslands in the Midwest, transforming these ecosystems with profound implications for climate dynamics. “Trees are great in the right place,” notes Susan Cook-Patton, a senior forest restoration scientist at The Nature Conservancy. “But they’re not uniformly awesome across the globe.”

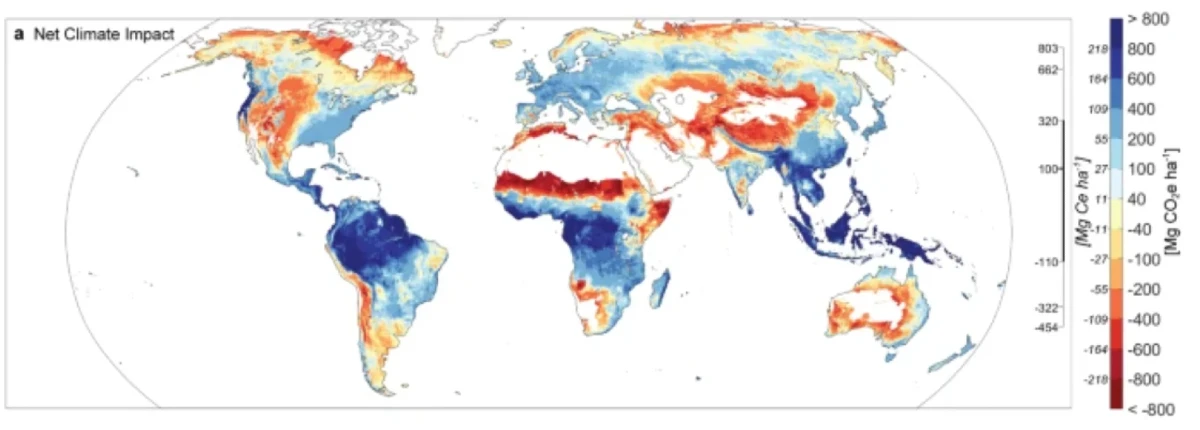

This spread of woody vegetation, referred to as the “Green Glacier,” threatens to overwhelm native prairies that are crucial for carbon sequestration and biodiversity. Researchers from Oklahoma to Texas report significant reductions in albedo—the Earth’s ability to reflect sunlight—as these darker trees replace the lighter-colored, reflective grasslands.

While trees are effective at pulling carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, their dark canopies absorb more solar energy. This absorption leads to local heating, offsetting the benefits of their carbon storage, especially in areas like Kansas where grasslands naturally cool the environment by reflecting sunlight.

“Our work in general suggests that adding trees to Kansas grasslands provides limited to no climate mitigation,” said Cook-Patton. In drier regions, the introduction of trees can even warm the climate, diminishing the benefits of their carbon storage significantly.

The Fight Against the Prairie “Green Glacier”

The rapid encroachment of trees not only heats the planet but also jeopardizes local agriculture, worsens wildfire risks, and destroys habitats for numerous grassland species. Efforts to conserve these open spaces are critical, not just for environmental health, but also for the communities that rely on these ecosystems for their livelihoods.

As cities and regions grapple with the best strategies for tree planting, the complex interplay of local climate impacts, carbon storage, and albedo changes necessitates a nuanced approach to reforestation and urban planning. “Trees can make it cooler locally,” remarked Chris Williams, a geography professor at Clark University, “but still warmer on a planetary scale.”

The Role of Trees in City Environments

In urban areas, the calculus for tree planting becomes even more complex. Cities plant trees for their ability to improve air quality, provide shade, and enhance quality of life by reducing the heat island effect. Yet, these benefits must be weighed against the broader climatic impacts, particularly in regions where increasing tree coverage might contribute to global warming.

Decision-makers are tasked with balancing these factors, considering both the immediate benefits of urban trees and their long-term impact on the planet’s climate system.

More To Discover

- U.S. Bets Big on Geothermal: $74M Investment Aims to Power Future with Earth’s Heat

- Carnegie Mellon Study Proves Grocery Delivery Is Less Sustainable than In-Store Shopping

- Wisconsin Scientists Innovate a Promising Solution to Extract Ammonia from Livestock Manure

- How New Tax Rules Will Make It Cheaper To Go Green And Connect To The Grid

Tools like the albedo and climate impact map created by researchers are vital for informing these decisions, ensuring that tree planting strategies are both effective and environmentally responsible.

As the debate continues, it’s clear that the role of trees in climate mitigation is as varied as the landscapes they inhabit. While they offer numerous benefits, in certain regions, the traditional view of trees as unalloyed climate heroes is being reevaluated, reflecting the complex realities of ecological management in a changing world.