On the coast of West Africa, the shores of Ghana aren’t just an embrace of the Atlantic. They tell a story—a narrative of the world’s discarded garments, each piece a testament to a global crisis. As the sun rises over Accra, the capital of Ghana, the city wakes to a tide of ‘obroni wawu’ – the clothes of dead white men, a local euphemism for the West’s cast-offs. This is the unseen aftermath of fast fashion, a journey that begins in high street shops and ends on the sands of West Africa.

The journey of these clothes begins thousands of miles away, in the charity shops and donation bins of the Western world. Laden with hope of a second life, they travel across oceans, only to confront a harsh reality upon arrival. As they spill into markets like old Fadama and Kantamanto, the scale of the issue becomes evident. While some garments find new owners, many more are destined for landfills, unable to withstand another cycle of use.

The Deluge of Western Cast-offs

In the heart of Accra, the day commences long before dawn breaks. Aisha Idrisu, cradling her young son, navigates through old Fadama, Accra’s largest slum. Her livelihood, like thousands of others, is tethered to the influx of second-hand clothes. These garments, once adorning shop windows in Europe and America, now pile up in the bustling markets of Accra.

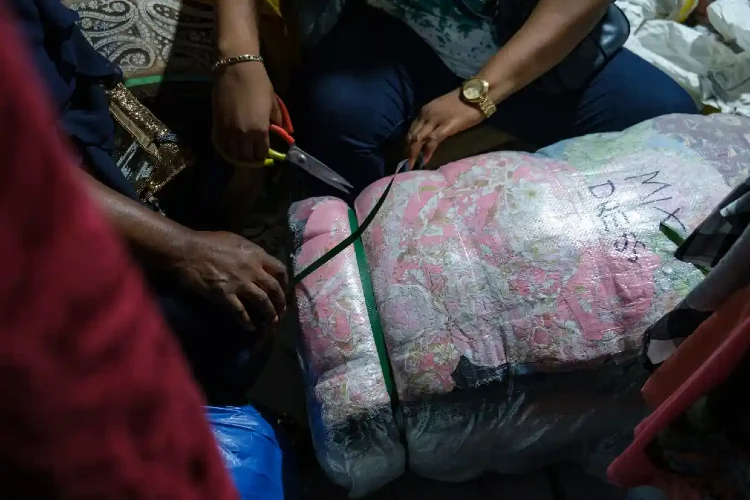

For importers like Asari Asamoa, the trade is a gamble—containers filled with the promise of profit or the peril of loss. Bales of clothing, each a mystery box of sorts, are their stock-in-trade. But buried within the bales are signs of a troubling reality—many of these clothes are destined for the landfill, unwearable, unwanted.

Their stories represent thousands more, for whom these clothes are both a lifeline and a burden.

The Required Toxic Embrace That Left Little Choice

Ghana’s embrace of the second-hand clothing trade has turned parts of its landscape into a toxic dump.

The unwanted fashion, unable to find a second life, becomes an environmental burden. The sprawling Kantamanto Market, the epicenter of this trade, is a labyrinth of commerce, but beneath its vibrant surface lies a darker truth.

Each day, mountains of unsold clothing are swept up, a vivid illustration of the waste crisis. The city’s waste manager, Solomon Oy, paints a grim picture: nearly 40 percent of the shipments turn into waste, an environmental calamity unfolding in real time.

For traders like Aisha, the influx of used clothing is a double-edged sword. It provides a livelihood, yet the deteriorating quality of imports makes the trade increasingly precarious. The streets of Accra are lined with vendors, each hoping to salvage something sellable from the bales. But as the quality declines, so does their hope of making a decent living.

As the world’s largest importer of used clothes from the United States and Europe, Ghana imports an average of 15 million items of secondhand clothing every week. In 2022, Ghana imported more than $220 million (£180m) worth of used clothes that failed to sell at thrift stores and charity shops.

The Stranglehold on Local Industry and Ecosystems

As the Western world’s discarded clothes flood Ghana’s markets, they strangle local industries.

Traditional textile makers, once the pride of Ghanaian culture, struggle to compete against the avalanche of cheap imports. The result is a cultural shift—local fabrics and designs, once a staple of everyday life, are now relegated to the realm of the special occasion, a luxury out of reach for the average Ghanaian.

The traditional Ghanaian attire, rich in color and history, is now a symbol of luxury, pushed aside by the affordability and accessibility of Western clothes personifying their fading cultural heritage.

The environmental toll is equally staggering.

During the rainy seasons, the discarded clothes clog the city’s sewers, turning waterways into textile graveyards. The impact on aquatic life is devastating—a silent catastrophe unfolding beneath the waves.

Looking Towards Solutions

The crisis in Ghana is a stark reminder of the global consequences of fast fashion. It calls for a collective awakening—a reevaluation of the fashion industry’s overproduction and the West’s consumption habits. There’s a need for sustainable practices in clothing donation and a shift towards supporting local textile industries.

Local initiatives in Ghana are emerging, aimed at better managing textile waste and reviving the traditional textile industry. But there’s little funding to power success on a truly helpful scale.

And while globally, there’s a growing movement advocating for sustainable fashion, urging consumers and brands alike to consider the lifecycle of their garments, those living in the slums of Ghana, have experienced no reductions in the cast-off used garments Western shoppers bought, never wore, and tossed away.

More To Discover

- FTC Report: Grocery Stores Boosting Profits, Driving Up Food Prices While Falsely Blaming Inflation, Supply

- Earth’s Northern Crown At Risk: Our Largest Continuous Expanse of Wilderness Is Shrinking

- The Future of Eggs Is Here: Precision Fermentation Means Flocks Won’t Need To Produce Eggs

- New Tech From US Researchers Transform Dandelions and Shrubs Into High-Performance Rubber Tires

The story of Ghana and its relationship with the West’s discarded clothes is a complex tapestry woven from threads of hope, despair, resilience, and responsibility, reflecting the unseen costs of our fashion choices and continuous overconsumption. It’s a narrative that calls for a collective awakening to the unseen costs of our fashion choices and a shared commitment to a future where sustainability and respect for both people and the planet are in vogue.

As the world grapples with the consequences of fast fashion, we must find a balance—a path that respects both the planet and the people who call it home, particularly those caught in the crossfire of global trade.