While hosting COP28, a UAE company, spent $2 billion to take carbon credits for pre-existing forests in Kenya, Liberia, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe. NGOs and environmentalists are accusing the Emirati government of ‘greenwashing’ and ‘colonialism’.

In a move that’s raising eyebrows and sparking debates, the United Arab Emirates, an oil-rich nation known more for its glittering skyscrapers than green initiatives, is now venturing into African forests. But wait, there’s a twist – it’s not for conservation, but for carbon credits. As the UAE hosts COP28, an Emirati company, Blue Carbon LLC, is signing deals left, right, and center with African nations like Kenya, Liberia, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. The goal? To turn parts of their pre-existing lush forests into carbon credits. But here’s the kicker – some NGOs are crying foul, calling it ‘greenwashing’ and even ‘colonialism.’

Picture this: Sheikh Ahmed Dalmook al-Maktoum, a young Dubai royal, casually shaking hands with the Liberian finance minister, all smiles for the cameras on March 25. But behind that handshake lies a deal of mammoth proportions. Blue Carbon LLC, under the sheikh’s leadership, has snagged exclusive rights to a whopping one million hectares of Liberian forests. That’s 10% of Liberia’s forest area, folks, and they’ve got it for 30 years.

The prince, in a statement oozing with ambition, told the Emirati press that this deal is a “milestone for Blue Carbon.” The plan sounds grand – to aid the world in transitioning to a low-carbon economy, helping governments hit their Net Zero targets. It all ties back to the Paris Agreement’s Article 6, which, in layman’s terms, is like a carbon credit marketplace. Countries that cut down their emissions more than expected can sell these excess reductions as credits. And who’s buying? Countries that aren’t cutting emissions as much. It’s like environmental Robin Hood, but instead of robbing the rich, we’re trading carbon credits.

As we peel back the layers of this deal, there’s a lot to unpack. Is this genuine environmental stewardship or a savvy business maneuver under the guise of a green initiative? With COP28 here, all eyes are on the UAE and its African forest takeover. It’s a story of forests, carbon credits, and perhaps a new chapter in environmental diplomacy, sprinkled with a bit of controversy and a dash of sass. Stay tuned as we dive deeper into what this all means for the African forests and the global fight against climate change.

Side-Stepping Responsibilities With A Greenwashed Loophole

‘Escaping responsibilities’ – a phrase that’s becoming increasingly synonymous with the world of carbon credits, especially in the context of the United Arab Emirates’ recent foray into African forests. Jutta Kill, a biologist and carbon market specialist, pulls no punches when discussing this contentious issue. She asserts that the concept of offsetting emissions through carbon credits, as sanctioned by the Paris Agreement, essentially lets industrialized nations dodge their environmental duties. Why? Because they can simply buy their way out of trouble.

Now, let’s talk about Blue Carbon LLC, the company at the heart of this saga.

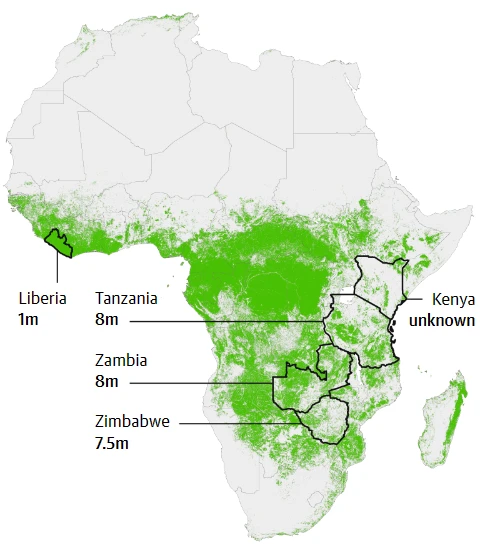

Established in August 2022, it’s like the new kid on the block that’s quickly becoming the popular one. In a stunningly short time, thanks to massive oil wealth, Blue Carbon has inked agreements with not one, but five African nations for forest management projects. We’re talking a mind-boggling 25 million hectares here, folks – almost half the size of France, and larger than the UK. This includes 10% of Liberia’s total surface area, millions of acres in Kenya, 10% of Tanzania, 10% of Zambia, and a staggering 20% of Zimbabwe.

But before you think it’s all set in stone, hold your horses. These deals are still in the preliminary stages. The big rulebook on carbon credit trading is expected to be unveiled at COP28, hosted by the UAE, starting November 30. Erika Lennon, a researcher at the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL) in the U.S., points out that the world is still waiting for the nitty-gritty details on how to use this tool effectively, including aspects like project registration and monitoring.

Blue Carbon, meanwhile, is on tenterhooks for the “Article 6.4 operationalization.” This fancy term refers to the establishment of a global carbon market, overseen by a body under the United Nations. Though officially a private entity separate from the Emirati state, Blue Carbon clarifies that the carbon credits from its projects aren’t just for the UAE’s benefit, but for various countries.

As we delve deeper, the plot thickens. Is Blue Carbon’s rapid expansion in Africa a pioneering environmental effort or a shrewd business move in a globally competitive carbon market? The answers might start to unfold at COP28, but one thing’s for sure – the debate over carbon credits, environmental responsibility, and the role of wealthy nations is far from over. Stay tuned as we continue to unravel the layers of this environmental and economic saga.

The Expensive Transition From Breaking The Rules To Making The Rules

From breaking to making the rules is exactly what the world is witnessing with the United Arab Emirates in the global carbon credit scene. Blue Carbon LLC, the company snapping up African forest rights for carbon credits, might just be the new player in town, but its connections run deep. The founder’s family ties and a peek at a confidential draft of an agreement between Blue Carbon and Liberia hint at a cozy relationship between the company’s ambitions and UAE’s interests.

When nudged about this, Blue Carbon played it cool, brushing it off as “a mere draft.” But if this agreement sees the light of day, it’s just another piece in the UAE’s growing carbon credit puzzle. Back in June, a posse of big Emirati companies formed the UAE Carbon Alliance, eyeing the creation of a national carbon market. By September, they were already talking big numbers – like $441 million (€410 million) in African carbon credits by 2030.

Why this sudden interest from the world’s 7th-largest oil producer, you ask? Well, the UAE isn’t planning to quit the oil game, the main villain in the climate change story. But they’re not content sitting on the sidelines of climate talks, either. They’re playing a more nuanced game now.

Li-Chen Sim, from the American think-tank Middle East Institute, puts it starkly. The UAE, once a staunch defender of fossil fuels, is now positioning itself as a shaper of rules in climate negotiations, particularly as COP28’s host. They’re subtly influencing the dialogue around fossil fuels, ensuring they remain part of the energy mix.

Leading the charge at COP28 is none other than Sultan al-Jaber, the UAE’s industry minister and CEO of Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC). And guess what? In November 2022, ADNOC announced its plan to ramp up oil production to a staggering 5 million barrels per day by 2027.

So, what do we have here? A fascinating mix of environmental ambition and oil interests, with the UAE straddling both worlds. As the host of COP28 and a key player in the global oil market, the UAE’s dual role is drawing both intrigue and scrutiny.

How A Massive Polluter Can Clean Up Their Image By Writing A Large Check

Paying their way to a greenwashed new image is actually a key strategy for the United Arab Emirates in the realm of carbon credits. As Souparna Lahiri from the Global Forest Coalition points out, the UAE is pushing hard to normalize the concept of offsets, a move that might just be their way of sidestepping calls to phase out fossil fuels. With several countries cozying up to Blue Carbon LLC, the UAE seems to be playing a savvy game of international chess.

However, not everyone is buying into this green narrative. Critics, like Alexandra Benjamin from the Dutch NGO Fern, are calling it out as a massive PR stunt to launder the image of big-time polluters. Benjamin doesn’t mince her words, suggesting that these carbon credits could fuel more fossil fuel production, thereby exacerbating the climate crisis. It’s like trying to put out a fire with gasoline.

But wait, there’s more. Doubts are also being cast on the actual effectiveness of these carbon credits. A joint investigation by SourceMaterial, The Guardian, and Die Zeit dropped a bombshell – apparently, a whopping 94% of credits from forest management projects are pretty much useless for the climate. That’s like buying a raincoat that doesn’t keep you dry.

The crux of the problem lies in how these projects calculate their impact. It’s all about the math – figuring out how much CO₂ would be released without the project versus the emissions the project can prevent. The difference is what gets sold as carbon credits. But here’s the catch: these aren’t hard facts, they’re estimates. And as Jutta Kill highlights, project developers might just have a vested interest in making their projects look better than they actually are.

Blue Carbon, for its part, is trying to distance itself from these criticisms. They’re urging NGOs not to lump them with the old guard, claiming they’re not following the same criticized frameworks. But they’re playing their cards close to the chest, keeping mum on what methods they’ll actually use.

So, what do we have here? A high-stakes game of carbon credits, international diplomacy, and environmental accountability, with the UAE and its partners trying to rewrite the rules. But as the debate rages on, one thing is clear – in the world of carbon offsetting, not all that glitters is green.

UAE’s Carbon Conquest of Africa

According to Axel Michaelowa from the University of Zurich, Blue Carbon LLC could churn out a staggering 250 million carbon credits annually. That’s enough to theoretically offset the entire CO₂ emissions of the UAE. But here’s where it gets thorny.

In Liberia, a million lives hang in the balance as Blue Carbon’s project threatens to upend their livelihoods. Fern, an NGO, points out the glaring issue: handing over land rights to Blue Carbon could trample the rights of those who depend on these forests for survival. This isn’t just an environmental issue; it’s a human rights one. In July, the Independent Coordination of Forest Monitoring, a collective of Liberian civil society groups, raised the alarm about this potential land rights violation.

The UN’s Christine Umutoni, stationed in Liberia, didn’t mince her words in a letter to the Liberian government. Skipping thorough public consultation, she warned, is a recipe for legal troubles, public backlash, and could even devalue the much-touted carbon credits.

But wait, there’s more. The financial split in this deal is raising some serious eyebrows.

Blue Carbon stands to pocket a whopping 70% of the revenue from carbon credit sales, leaving the Liberian government with just 30%. Andrew Zeleman of Liberia’s Community Forestry Development Committee hits the nail on the head with his question, “Who owns the forest?” He’s calling out what many see as a grossly unfair deal, where the local government and communities get the short end of the stick.

More To Discover

This situation has led NGOs like Fern to slam these practices as “carbon colonialism.” They argue that such deals not only snatch away the opportunity for these countries to use their forests for their own climate commitments, but are essentially large-scale land grabs – a misleading and ineffective solution to the climate crisis.

So, what started as a story about carbon credits and environmental initiatives has quickly unraveled into a complex web of ethical, financial, and ecological dilemmas. From the streets of the UAE to the forests of Liberia, this saga of carbon credits, rights, and profits is a potent reminder of the intricate and often contentious relationship between global environmental goals and local realities. Stay with us as we continue to bring you insights and updates on this unfolding story.