In a remarkable leap forward for agricultural science, a team of Swedish scientists from Linköping University has created a revolutionary form of “soil” known for its electrical conductivity, which has been shown to boost the growth of barley seedlings by an impressive 50% in just 15 days.

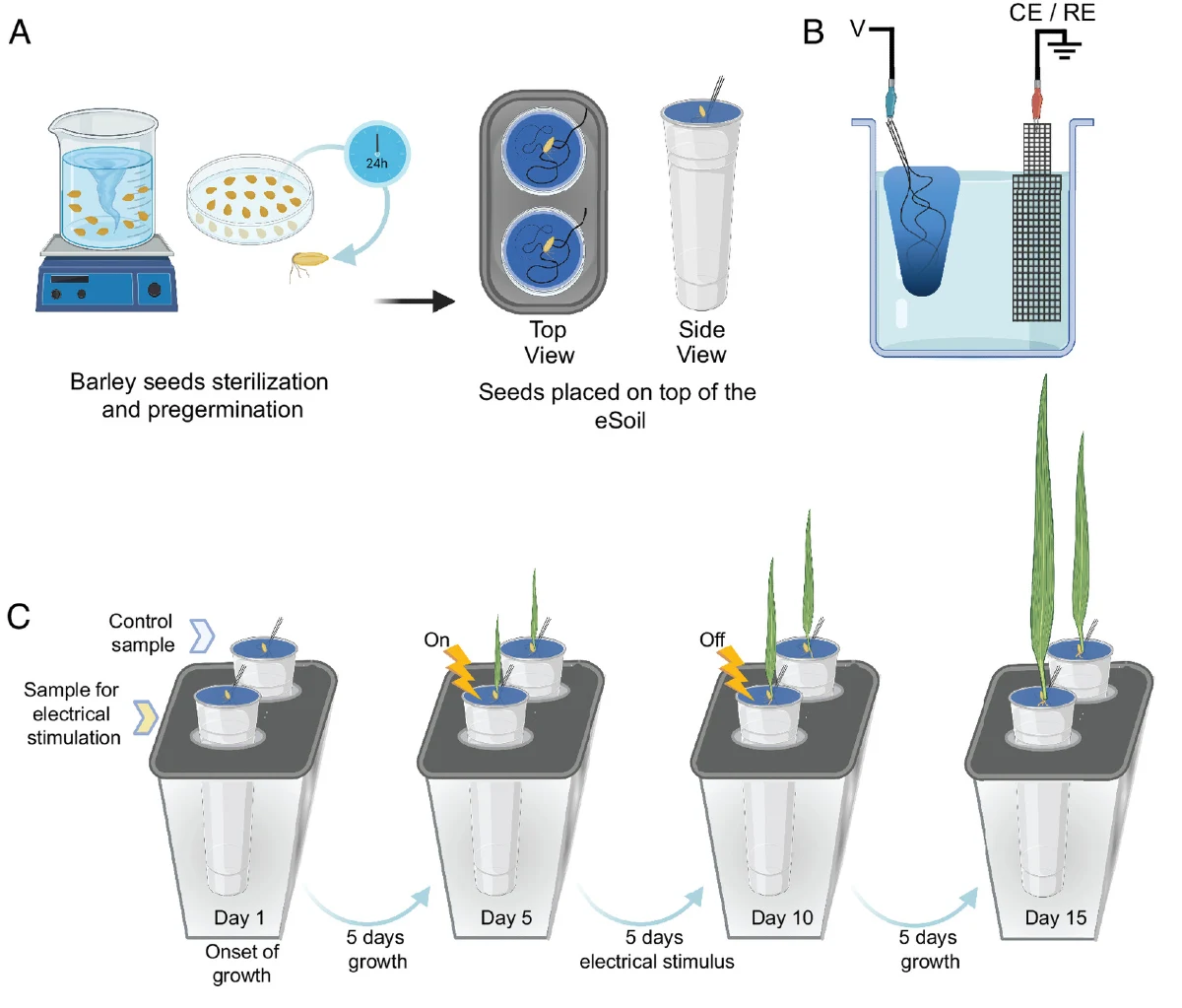

This thrilling innovation (no exaggeration) represents a significant advancement in the field of hydroponics, a soil-free farming method where plants are grown in a water-based, nutrient-rich solution. The key component of this new development is a unique cultivation substrate called eSoil, specifically designed for hydroponic systems.

Eleni Stavrinidou, an associate professor at Linköping University, emphasizes the critical role of this invention in addressing the urgent global food challenges posed by a growing population and climate change. “Our planet’s existing farming methods are insufficient to meet our future food requirements,” Stavrinidou notes.

Hydroponics offers a promising solution for growing food in urban environments, where space is limited, and conditions can be tightly controlled. eSoil, the innovative electrically conductive substrate developed by the team, is pivotal to this approach.

Their research, published in the prestigious journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, demonstrates that barley seedlings grow up to 50% faster over two weeks when their roots are subjected to electrical stimulation.

One of the most significant advantages of hydroponic farming is its soil-less nature. Plants are grown in a water-based environment, relying on this medium along with nutrients and a supportive substrate for root growth.

This system allows for the efficient recycling of water and precise delivery of nutrients to each plant, leading to reduced water usage and optimal nutrient use, making it a more sustainable option than traditional farming methods.

Another benefit of hydroponics is its potential for vertical farming. This space-saving approach involves growing crops in vertically stacked layers, which can be particularly useful in urban areas.

Although hydroponics has been successfully used for crops like lettuce, herbs, and some vegetables, it hasn’t been widely adopted for grain crops like barley, typically grown in soil.

The new study challenges this norm, showing that barley seedlings can thrive and grow faster in a hydroponic system with electrical stimulation.

Stavrinidou points out that while the exact biological mechanisms behind this accelerated growth aren’t fully understood, it’s clear that the seedlings process nitrogen more efficiently when electrically stimulated.

This efficient use of resources, however, requires further investigation to fully comprehend its implications.

In traditional hydroponics, mineral wool is commonly used as a substrate, but its production is energy-intensive and the material isn’t biodegradable.

This prompted the researchers to explore sustainable alternatives, leading to the development of eSoil. Made from cellulose, the most abundant biopolymer, combined with a conductive polymer called PEDOT, eSoil represents an eco-friendly and innovative approach to plant cultivation.

The unique aspect of this research is the use of a lower voltage for root stimulation compared to previous studies, making it more energy-efficient and safer. Stavrinidou sees this as just the beginning, with many more research opportunities on the horizon to further refine hydroponic farming techniques.

More To Discover

- 9 Trailblazers of Mycelium-Based Meats: 8 Young Fungi Brands You Can Eat Right Now And Their Godfather

- The Billion-Dollar Trust Issue: When the Price of Scientific Publishing Eclipses the Value of Knowledge

- UN Report Reveals World Falling Drastically Short on Climate Goals, Warns of Looming Catastrophe

- Bottled Water Industry Responds to Columbia University Study on Nanoplastics & They’re Not Wrong

She concludes with optimism, stating, “Hydroponics may not be the sole answer to global food security challenges, but its potential, particularly in areas with scarce arable land or harsh growing conditions, is enormous.”

Source: PNAS