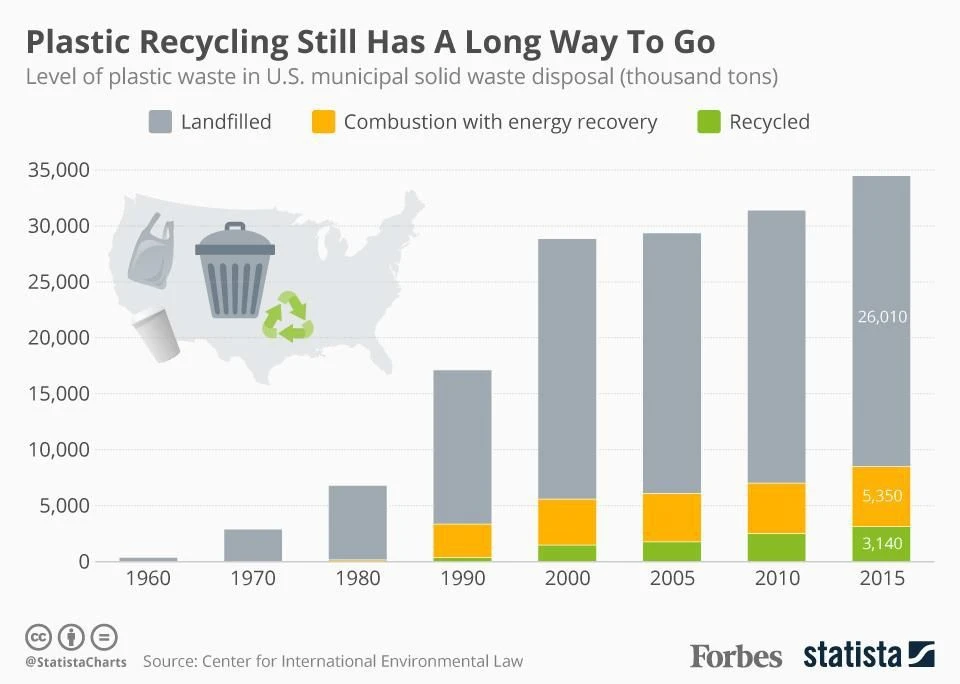

Jan Dell, a former chemical engineer turned environmental advocate, has been vocal about a misleading reality: “So many people, they see the recyclable label, and they put it in the recycle bin,” she states. “But the vast majority of plastics are not recycled.” Despite Americans generating approximately 48 million tons of plastic waste annually, only a meager 5 to 6 percent actually undergoes recycling, according to the Department of Energy.

Dell’s non-profit, The Last Beach Cleanup, targets the heart of this issue from her garage in Southern California, surrounded by deceptive recyclable-labeled plastics. “You’re being lied to,” she asserts, pointing out the misleading symbols on plastic products meant to imply recyclability.

This symbol, the chasing arrows, introduced in 1988, was part of a broader industry strategy not to enhance recycling efficacy but to boost public confidence in it. Davis Allen, an investigative researcher with the Center for Climate Integrity, clarifies, “They needed people to believe that it was working.” This laid the foundation for a deceptive narrative that recycling could handle the burgeoning plastic waste problem.

A groundbreaking report titled “The Fraud of Plastic Recycling” exposes this narrative as a facade. The plastics industry has long understood the “technical and economic limitations that make plastics unrecyclable” at scale, yet continued to promote recycling as a viable solution. Allen explains, “They couldn’t ever lie about the existence of plastic waste. But they created a lie about how we could solve it, and that was recycling.”

The inquiry raises a critical question: If plastic recycling is neither technically feasible nor economically sensible, why push it? Allen’s response is stark: “The plastics industry understands that selling recycling sells plastic, and they’ll say pretty much whatever they need to say to continue doing that. That’s how they make money.”

Historical documents and insider accounts unearthed by Allen reveal a consensus within the industry about the inefficacy of recycling. In one instance, a 1989 trade conference in Florida had an industry leader admitting, “Recycling cannot go on indefinitely, and does not solve the solid waste problem.” By 1994, an Exxon executive was candid about their commitment: “We are committed to the activities, but not committed to the results.”

Despite this, the industry has recently launched a new ad campaign titled “Recycling is real” and touts investing in so-called advanced recycling technology. The American Chemistry Council, defending against the criticisms, stated that “plastic makers are working hard to change the way that plastics are made and recycled,” dismissing the report as “flawed” and “outdated.”

Yet, skeptics like Dell remain unconvinced, dismissing the latest recycling initiatives as recycled promises: “It’s the same process they were trying 30 years ago, and my response to that is, it’s science fiction.”

With global plastic production projected to triple by 2050 and the environmental toll becoming increasingly untenable, over 170 countries are now rallying under a United Nations treaty to curb plastic pollution.

As the plastics industry lobbies against production bans while advocating for more recycling, Dell’s final remark resonates with poignant clarity: “The only thing the plastics industry has actually recycled is their lies over and over again.”