Picture yourself strolling through the cereal aisle of your local grocery store. An array of options spans before you, from sugary delights to fiber-packed health bombs. The breakfast cereal industry seems like a timeless staple of modern life, right? Well, buckle up, because the story behind it is more peculiar than you’d think.

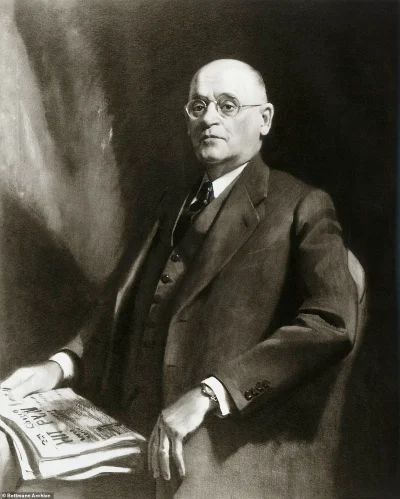

Of course, when we think of breakfast cereal, Kellogg’s immediately pops into mind. But here’s a twist: while W.K. Kellogg gets the official credit for founding the company, it was his brother, Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, who was the mad scientist – err, driving force – behind the birth of breakfast cereal.

And let me tell you, this tale is as far from a sugary narrative as you can get.

Imagine a mix of religious devotion, a dash of repressed natural urges, a sprinkle of distrust for conventional medicine, and a dollop of bizarre treatments that could make you cringe. Yep, that’s the story of John Harvey Kellogg.

On one hand, he was a crusader for health, on a quest to make the world a better place.

On the other hand, he dabbled in eugenics and flirted with the idea of sterilizing people he deemed “undesirable.”

His story tells us that history is a canvas painted with shades of gray, and that even in pursuit of noble goals, some folks take unexpected detours. Sometimes, those detours lead to building a business empire on rather unconventional foundations.

The Breakfast Blueprint: Rooted in Belief

To understand the enigma that was Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, we have to rewind the clock to his parents, John Preston Kellogg and Anne Stanley.

These two were farmers with a twist – devout souls teetering on the edge of a burgeoning religious movement. In 1852, they stumbled upon the beliefs of a radical new sect born from a rather anticlimactic date: October 22, 1844.

For a group known as the Millerites, that date was no ordinary day – it marked the anticipated return of Christ.

Picture this: believers anticipated Jesus to stride back into the world, and when that didn’t quite pan out, it was dubbed the “Great Disappointment.” Amidst this theological turbulence, a schism formed among followers.

Enter Ellen Harmon-White, a woman who claimed to have had a celestial revelation in December of that fateful year. She asserted that the date was indeed correct, and that the path to salvation was, quite literally, paved with righteousness.

The Millerites’ beliefs were a bit of a jumble when the Kelloggs hopped on board, but by 1863, the movement had consolidated into the Seventh-day Adventist church.

By then, the Kelloggs had become integral to the group, even helping relocate the budding church to Battle Creek, Michigan. It was there, in 1852, that the main character of our tale, John Harvey Kellogg, was born.

As the Seventh-day Adventist movement took shape, young John was front and center, ready to play his unique role in the intriguing drama that was unfolding.

From Printing Presses to Health Crusades: Dr. John Harvey Kellogg's Adventist Journey

It’s like a page out of an adventure story: young John Harvey Kellogg, only 12 years old, receives an invitation that would change the course of his life.

James White, co-founder of the Seventh-day Adventist movement and married to the visionary Ellen Harmon-White, sees potential in young Kellogg. He invites him to delve into the world of the printing trade, hoping that his skills would aid in the wide dissemination of their transformative teachings.

But John’s interests were as varied as the pages he’d soon be printing. While he was deeply engaged with the Adventist teachings, he was also captivated by the writings of earlier health reformers. These reformers advocated temperance, vegetarianism, and abstinence, all aimed at bringing humans closer to the divine. These ideas found harmony with the burgeoning Seventh-day Adventist beliefs.

This was the genesis of Kellogg’s ascent within the Adventist hierarchy. To grasp the events that follow, it’s crucial to understand his foundational beliefs. In the Seventh-day Adventist tradition, leading a wholesome, healthy life is a moral imperative.

The body, they assert, is the vessel for serving God, and maintaining it optimally ensures the capacity for complete service. This includes abstaining from alcohol and tobacco – staples of the era’s lifestyle.

However, there was more to this narrative in Kellogg’s time. Adventist leaders were skeptical of conventional medicine, aiming to cultivate a cadre of doctors rooted in Adventist principles yet well-versed in practical medicine.

This aspiration led to Kellogg’s involvement in a unique journey. He was selected to study at the Hygieo-Therapeutic College in New Jersey, followed by the University of Michigan Medical School.

Now, here’s the twist: Kellogg didn’t envision himself as the stereotypical doctor, curing ailments. Instead, his goal was prevention.

He earned his M.D. from Bellevue Hospital Medical College in New York City in 1875. By then, he was already an author, penning a cookbook advocating improved diets, and a proponent of vegetarianism. He also took on the role of editor for a monthly Adventist publication, he aptly named Good Health.

The Sanitarium Saga: Where Health and Healing Converged

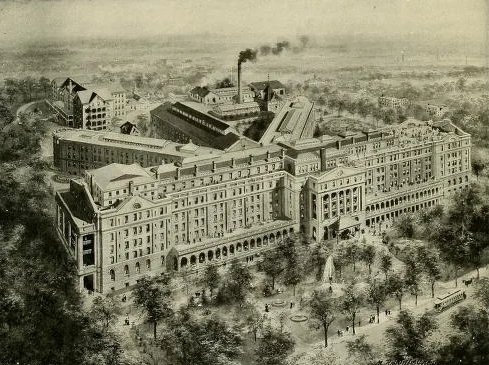

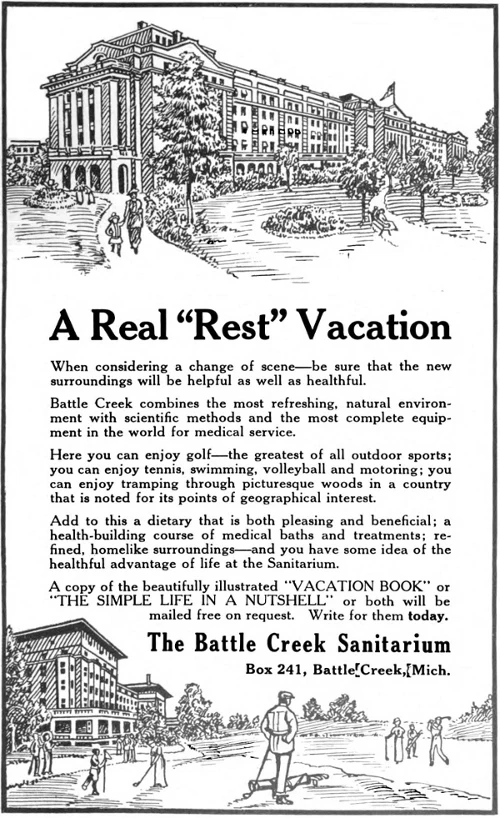

In 1876, Kellogg stepped into a role that would cement his legacy. He became the superintendent of what was initially the Western Health Reform Institute, later christened the Battle Creek Sanitarium. This wasn’t merely a medical institution – it was a revolutionary concept, part resort, part medical facility, and part haven for the influential elite.

Hold onto your seats, because here’s the kicker: at its zenith, the Battle Creek Sanitarium was welcoming a staggering 12,000 to 15,000 new patients annually. And among this influx of health seekers were some history-makers, faces that left an indelible mark on the world.

Picture this: Henry Ford, the titan of automobiles, walking the same halls as Thomas Edison, the luminary inventor. Political giants like John D. Rockefeller and Warren Harding, mingling with the trailblazing Booker T. Washington and the indomitable Sojourner Truth.

What might seem like a health retreat was, in fact, a melting pot of brilliance, where minds met and health discoveries brewed. And right at the center of it all was the enigmatic Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, orchestrating this curious symphony of health, healing, and human history.

The Marvelous Madness of Kellogg's Sanitarium

Hold onto your hats, because even the daring Amelia Earhart took a pit stop at Dr. Kellogg’s retreat for a bit of rest and rejuvenation, a ritual endearingly dubbed “taking the cure.” Brace yourself, because the grandeur of the facility was nothing short of astonishing. When we say “impressive,” we’re dancing on the edge of an understatement.

Imagine this: a 15-story tower, a whopping 1200 beds, an indoor jungle of greenery, a lobby stretching as vast as a football field, and here’s the pièce de résistance – a jaw-dropping five acres of marble floors.

You read that right, five acres!

But wait, there’s more. This wasn’t just a health haven; it was an entire microcosm. The sanitarium boasted its own power plant, an assembly of professionals including doctors, nurses, masseuses, and orderlies.

And reigning over this health empire was none other than Dr. Kellogg himself. He greeted every patient who disembarked from the train and was delivered into his care by horse-drawn coaches.

Picture this, a regal doctor meeting patients with all the pomp and circumstance of a bygone era.

But now, let’s dive into the rabbit hole of Kellogg’s treatments. Buckle up, because things are about to get, well, peculiar.

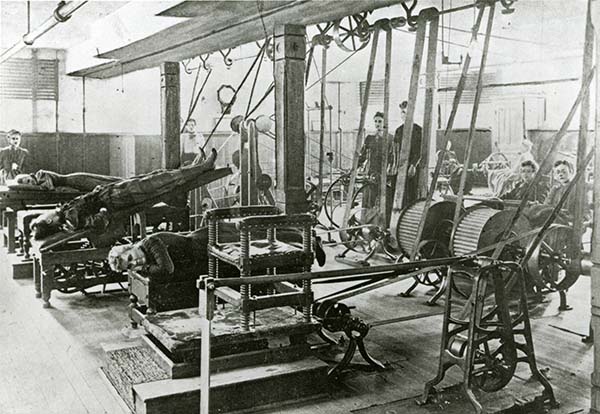

The sanitarium was equipped with all the apparatuses required to whip patients into the pinnacle of health, but these treatments weren’t exactly your run-of-the-mill prescriptions.

Enter the “sanctum sanctorum,” a room that was, believe it or not, dedicated to enema machines.

Yes, you read that correctly. These contraptions could pump a whopping 15 quarts of water where the sun doesn’t shine in just a single minute.

If that doesn’t nudge you towards reaching for a high-fiber cereal, what will?

And if patients weren’t hitting Kellogg’s desired four bowel movements per day – a number he gleaned from observing apes – then it was time for yogurt.

First, a pint of yogurt was incorporated into the daily menu, followed by a yogurt enema.

Why, you ask? Cleanliness, my friends, was Kellogg’s obsession. Those marble floors weren’t just for show; they were a barrier against lurking “germs and vermin.”

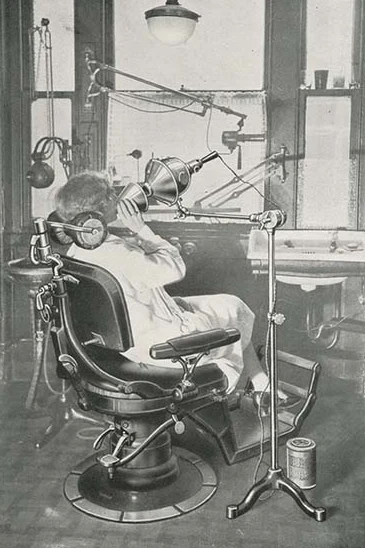

Enemas were just the tip of the iceberg in the land of Kellogg! Light therapy was also in vogue, including Kellogg’s own invention: the electric light bath.

Imagine patients ensconced in a cabinet bathed in light bulbs. It was touted as a cure-all for everything from writer’s cramp to the more serious affliction of syphilis.

And here’s something unexpected – it’s not as absurd as it sounds. Kellogg’s explorations laid the groundwork for using light therapy to combat depression.

But let’s not stop there – electricity was another of Kellogg’s muses. He prescribed sinusoidal current treatments, a mild electric therapy, for patients grappling with tuberculosis and lead poisoning.

Armed with a homemade device fashioned from a telephone, the current would sometimes flow onto the skin, and in more daring scenarios, straight into the eyeballs, all in the name of treating ocular ailments.

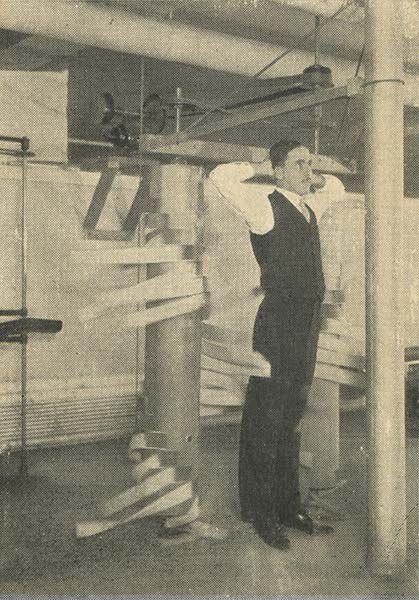

And if you thought machines that vibrated, shook, slapped, and yes, even beat patients were beyond belief, think again.

These contraptions aimed to stimulate circulation, reinvigorate the bowels, and let’s not forget, make the sanitarium a bastion of unconventional wellness.

So, there you have it, the marvels and mysteries of Kellogg’s health haven.

In the end, this was no ordinary sanitarium – it was a place where medical curiosity and bizarre treatments intertwined, and it all unfolded under the watchful gaze of the illustrious Dr. John Harvey Kellogg.

The Presidential Connection: Dr. Kellogg's Machine Marvels and Controversial Cures

Not only did Dr. Kellogg’s patients flock to his remarkable sanitarium, but some of his well-healed patrons took the treatments home with them.

Calvin Coolidge, for instance, had his own version of Kellogg’s contraptions right in the White House, during his presidential reign. And here’s the kicker: the clinic itself was fondly referred to as the “San” by those who frequented its halls.

Dr. Kellogg wasn’t just tinkering for the fun of it – his treatments had legions of believers. In the span of a few years, he surged from treating a mere 300 patients annually to a whopping 1,200, and the numbers just kept spiraling.

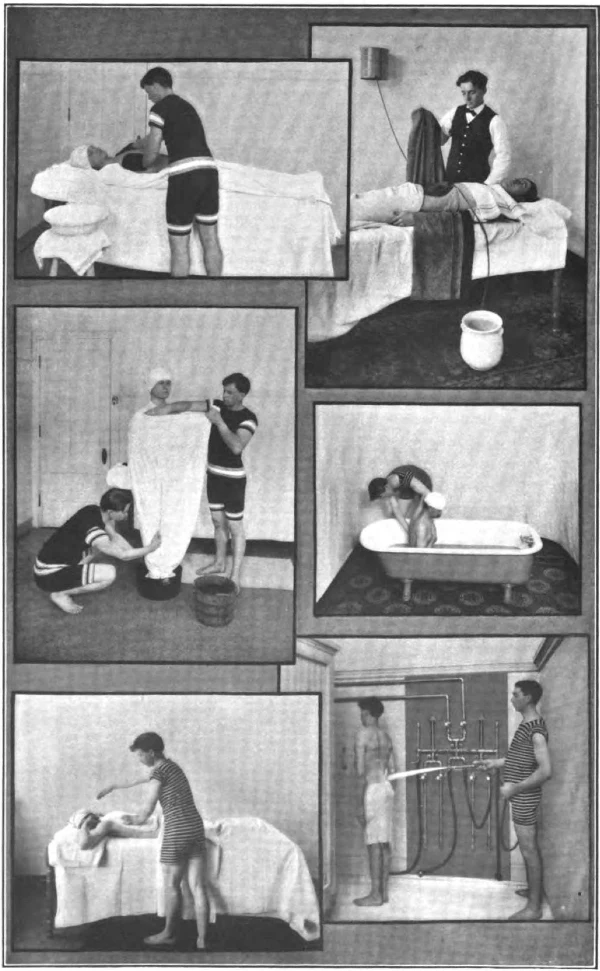

His faith in his methods was unshakable, and he even took to advertising in major magazines to broadcast the miracles of his treatments. A 1907 Good Housekeeping advertisement boasted about the mind-boggling 46 different kinds of baths at Kellogg’s disposal.

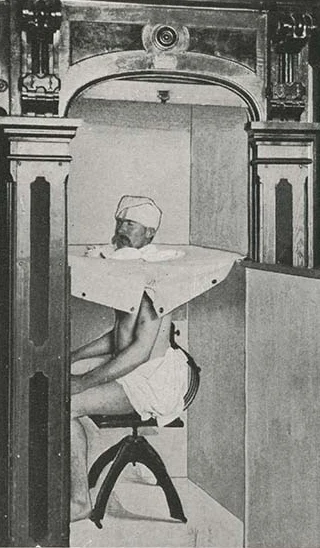

Now, let’s venture into the bizarre – Kellogg’s baths were a genre all their own. You had your run-of-the-mill foot baths, the curious light baths, and then you had the extraordinary: the continuous bath.

So, it’s like that relaxing bath after work you enjoy so much, just with one small change… it may never end!

A patient might find themselves soaking for days or even months on end. Yes, you read that correctly – days, possibly months. The longer you mull over it, the stranger it seems. But buckle up, because this isn’t the strangest prescription in Kellogg’s arsenal.

Enter “the solitary vice.” Dr. Kellogg believed that the act of masturbation was the gateway to afflictions such as heart disease and, yes, even insanity. His remedy isn’t for the faint of heart!

He subjected patients with a chronic habit to a series of agonizing interventions.

Boys were bound, tied, or subjected to wearing cages, all in a bid to curb their actions.

And if that didn’t sound nightmarish enough, Kellogg upped the ante: circumcision without anesthesia, in the fervent hope that the agony would deter any future indulgence.

Girls were not exempt, either, and some were burned with acid or subjected to surgery to remove part of the genitals.

Yes, you read that right. The same man who championed wellness and health through unconventional means also dabbled in the unorthodox and, to many, horrifying. His legacy is as controversial as it is astonishing, a reminder that even the most visionary minds can veer into the realms of the unthinkable.

Kellogg was devoted to health and godliness, and he was extreme. Amid these cures, Kellogg also focused on something that he believed desperately needed an overhaul: breakfast.

Changing the Way America Ate To Cure It All

John Harvey Kellogg - Corn Cereals and Crazy Medicine

This is where we go back to the heart of Kellogg’s Seventh-day Adventist beliefs. Co-founder Ellen Harmon White wrote that the truly devout would follow a vegetarian diet, because fruit and vegetables were seen as God’s gift to mankind.

She taught that people should eat foods that could be consumed in their natural state: fruits, vegetables, nuts, and grains.

Kellogg followed that belief, at a time when breakfast was about as unhealthy as you can imagine. Kellogg, remember, was living at a time when most people started their day with the previous nights’ leftovers.

Some of the most common breakfasts involved meat and potatoes reheated in a pan with whatever fats they had congealed in.

Heavy meals of salted and cured meats were also popular, and anything grain-based was difficult.

It was time-consuming and labor-intensive, and it meant getting up before the sun, stirring and cooking raw grains into gruel.

In 1858, Walt Whitman wrote that indigestion was “the great American evil,” and it’s no wonder. Gastrointestinal distress was so common and so frequent, there was one catch-all term used to describe all the symptoms: dyspepsia.

Kellogg’s attempts at overhauling breakfast were practical: he wanted something that was easy for someone to prepare, and just as easy on the stomach.

He and his brother spent years experimenting in their own food lab, trying to come up with vegetarian diets that would be easy for any patient to digest, and that were boring.

The boring part was on purpose.

Part of the theory was that bland, boring food would not only keep their patients walking the straight and narrow right up into heaven by consuming food in the way God meant, but also that it would prevent them from getting too excited and overstimulated.

Rise of the Crunch: Kellogg's Cereal Revolution

Behold, the dawn of success – let’s take a peek at Kellogg’s culinary victories, starting with none other than “protose.” Imagine a primitive rendition of today’s veggie burger, flavored with the nutty essence of peanuts.

This pioneering creation wasn’t just confined to the confines of the sanitarium; it even graced mail-order catalogs, reaching eager patrons beyond the walls.

But the story doesn’t end here. Kellogg had another innovation brewing – enter “granula.” This concoction, a medley of corn meal and oatmeal, was baked before being ground into bite-sized bits.

Unfortunately, the name faced a legal skirmish, leading to a swift renaming. Thus, “granula” gracefully morphed into the term we now know and love: “granola.”

Yet, the stars of the show were still waiting in the wings – those delightful flakes we’ve all come to associate with Kellogg’s. Legend and history intersect in the captivating tale of their inception.

The Kellogg brothers inadvertently left wheat-berry dough out overnight. Come morning, the dough had gone stale, and innovation struck when they toasted and rolled it out.

Voilà! Crunchy flakes were born, causing a sensation among their patients.

As the cereal business gained momentum, Kellogg handed over the reins of marketing to his brother, a bookkeeper at the sanitarium.

However, all wasn’t rosy at the Battle Creek Sanitarium.

Tensions escalated with mounting debts, and concerns arose over a curriculum that seemed to drift from its Seventh-day Adventist roots.

Then, tragedy struck as a fire razed the compound, leaving Kellogg with the news that the sanitarium wouldn’t be rebuilt.

1902 Battle Creek Sanitarium Fire

On February 18, 1902, the Battle Creek Sanitarium was ablaze. The firemen knew it wasn’t an ordinary fire as the red glare painted the snow.

The old building, with its open elevator shafts, vast corridors, and a drafty tunnel, proved ideal for fire. Within hours, the Sanitarium, hospital, a corset-manufacturing house, and smaller structures were all engulfed.

Despite the chaos, patients orderly exited, thanks to devoted staff and fire escapes. Gospel singer Ira D. Sankey barely escaped, guests saved their lives but lost possessions.

Precious equipment, including sentimental oil paintings, historical mementos, and Evangelist Stucker’s sermons, vanished. Half a million dollars’ worth of diamonds also went up in smoke.

Dr. Kellogg, arriving the next morning, pledged to rebuild. Legend says he had rough plans in his pocket, signaling his commitment to restoring the Sanitarium.

Meanwhile, on the business front, Kellogg’s brother, Will, championed an ingenious yet contentious idea – adding sugar to their corn flakes.

The mere thought horrified Kellogg, who viewed such an addition as sacrilege. This difference in opinion ultimately led to a division: Will departed to found the Battle Creek Toasted Corn Flake Company, while Kellogg embarked on his own cereal-selling venture.

A twist of fate added intrigue to this saga.

Will initiated a lawsuit against Kellogg, triumphing and launching his cereal business.

Meanwhile, John Harvey Kellogg continued his work at the sanitarium. It’s worth taking a pause here to acknowledge that Kellogg’s wasn’t the sole cereal company to emerge from this transformative era.

Rivalry and Revolution: The Cereal Showdown

Enter Charles William Post, a recurring figure in the Kellogg saga. During the 1890s, Post sought refuge at the sanitarium amid bouts of mental distress and stress.

Witnessing the unconventional practices unfolding within its walls, Post identified a burgeoning trend. Inspired by Kellogg’s vision, he founded his own enterprise, introducing the world to Postum and Grape-Nuts cereals.

The Kellogg brothers created flaked cereal. The potential for business success was evident, and W.K. Kellogg wanted to keep it confidential.

His brother, John, however, allowed public observation of the flaking process by any guest at the sanitarium. One guest in particular, C. W. Post, took note and later replicated the process for his company.

Post’s company evolved into Post Cereals and eventually General Foods, marking the origin of Post’s substantial fortune.

W.K. was so upset that he resigned from the sanitarium to establish his own company, Battle Creek Toasted Corn Flake Company, which, over time, became Kellogg’s.

Post’s company played a pivotal role in catalyzing Kellogg’s drive to craft better, longer-lasting products.

In his own words, Kellogg declared, “I am not after the business; I am after the reform; that is what I want to see.” Kellogg’s reformist fervor led to the imposition of strict rules upon his patients.

This included adherence to his ascetic, vegetarian diet, as well as an intriguing mandate: copious chewing.

Firmly aligned with the principles of Horace Fletcher, Kellogg championed the art of Fletcherism – advocating a rigorous 40-chew regimen for each morsel of food consumed.

So fervent was his belief in this practice that he would often lead diners in a merry rendition of his “Chewing Song.” However, not every patient sang praises for his dietary dictates or his prohibitionist stance on alcohol and smoking.

Fortunately for the dissenters, an astute entrepreneur seized the opportunity, establishing the Red Onion Tavern just a stone’s throw away.

This establishment catered to those yearning for steaks, cigars, and a swig of whiskey, all served with a promise of speedy service to beat the sanitarium’s nightly curfew of 11 pm.

While John Harvey Kellogg was synonymous with the Battle Creek Sanitarium, his life wasn’t confined to an unending procession of patients.

Picture this: Kellogg, a striking figure, donning his signature pristine white suit adorned with an exotic cockatoo perched upon his shoulder. It was an unforgettable sight as he delved into consultations with those seeking his insights.

However, the man behind the sanitarium also had a life beyond its walls – a life that extended into eugenics.

Kellogg's Life Beyond the Sanitarium (Enter Eugenics)

In the tapestry of his life, John Harvey Kellogg’s journey extended beyond the confines of the Battle Creek Sanitarium.

In 1879, he tied the knot with Ella Eaton. Though they didn’t have biological offspring, their home embraced the laughter and warmth of more than 40 foster children, some of whom they officially adopted.

Ella proved to be an essential partner in Kellogg’s dietary pursuits, offering both inspiration and assistance. Her influence also extended into new social circles, such as the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union.

But there was more to Kellogg than healing through food.

His skillful hands led him into the realm of surgery, with stints in London and Vienna to study abdominal procedures.

Remarkably, by the time he finally retired his surgeon’s scalpel at the age of 88, he had conducted around 22,000 surgeries.

His dedication to the art of healing left an indelible mark on the field.

Yet, Kellogg’s path took an unexpected turn in 1907, as he found himself at odds with his Adventist church leaders. Their disagreement escalated to the point of his expulsion from the church.

The core of their discord lay in his alleged misuse of church funds for medical research and education, straying from the church’s evangelistic mission.

Not one to be easily swayed, Kellogg maintained his grip on the sanitarium’s reins.

While remaining a formidable presence there, he extended his influence by establishing schools for hygiene, nursing, home economics, and physical education on the sanitarium grounds.

His commitment to public health also led him to serve on the Michigan State Board of Health, a role that complemented his prolific writing endeavors. Over the course of his life, he authored approximately 50 books on health-related topics and was an early advocate against smoking’s dangers.

But history, at times, unfolds its darker shades. As the story unfurls, a startling chapter emerges – Kellogg’s involvement in the formation of the Race Betterment Foundation. Alas, its purpose was as unsettling as it sounds: it focused on advancing the perceived superiority of specific races through selective breeding.

Those foster children welcomed into the Kellogg household carried a somber undertone.

As the Eugenics Archives reveal, many of these children were classified as “undesirables” for various reasons. Kellogg’s intentions were far from purely altruistic. His aspiration was to unravel the intricate interplay of heredity and environment, leading him down a controversial path.

And there’s more to this story, for the Battle Creek Sanitarium served as a central hub for the propagation of eugenics across the United States in the early 20th century.

With around 30 years and a considerable financial investment, Kellogg ardently advocated for the exclusion of individuals possessing specific genetic traits from the human breeding pool, all under the belief that such actions would elevate humanity as a whole.

Exclude them how?

While he was serving on the Michigan State Board of Health, he successfully lobbied to pass a law that would call for the “sterilization of mentally defective persons”, a law that led to the involuntary sterilization of at least 3,800 people in the state.

Kellogg — and other believers — preached that encouraging only certain people to reproduce would end all the ills the human race suffered from, from poverty to criminality to, quote, “feeblemindedness”.

That superior race was, of course, the Caucasian one and yes, there was a very real association that would later form with the Nazi party. Kellogg began to completely embrace eugenics after his falling-out with the Seventh-day Adventists — a group who, incidentally, believed that all life was a gift from God.

He became obsessed with the idea that if things continued as they were, mankind would begin to decay and degrade in quality until finally, it simply ceased to exist.

In 1914, Kellogg had become good friends with other leading figures of the eugenics movement, like Charles Davenport, founder of the Eugenics Record Office.

They held the first Race Betterment Conference, and one of his guest speakers was a former patient — Booker T. Washington was there to try to talk to attendees and convince them that everyone should be treated fairly and equally. The San, incidentally, was always a segregated facility.

Conference attendees did more than just examine and measure around 5,000 children as a part of the “Better Babies” contest, they also made it clear they were going to start pushing their ideas further into the US.

The second conference was held in 1915 at the Panama-Pacific International Exhibition, and it took the society’s beliefs — clearly illustrated by charts highlighting the differences between “superior” and “degenerate” races — and put them squarely in front of 18 million visitors.

He campaigned for the establishment of a nationwide legislature similar to what he had established in Michigan, and even proposed a registry where people would be given “pedigrees,” and parents who fell within the established guidelines for “racial hygiene” would be eligible for awards.

There were a few things that brought down the eugenics movement, and the first was the extremes of Nazi Germany. Even before that, the troubles brought by the Great Depression proved to many that poverty and hardship had nothing to do with genetics, but eugenics legislation was still in place — and sterilizations were practiced well into the 1970s.

As for Kellogg, he died in 1943. He nearly hit the century he had always proclaimed he would live to: he was 91 years old.

Dr. Kellogg left behind a legacy that encompassed groundbreaking health reforms, pioneering breakfast cereals, and, advocacy for an extremist ideology that cast a shadow over his accomplishments.