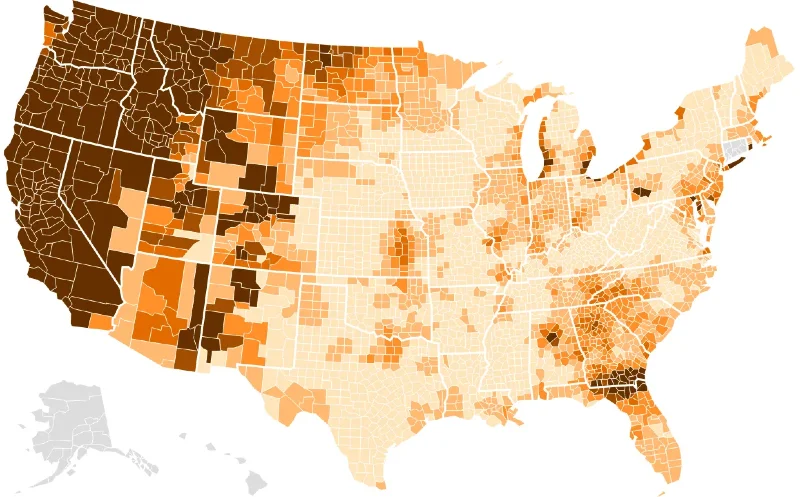

In an era where the quest for cleaner air seemed to be making significant strides, climate change is poised to reverse those gains, casting a shadow over the United States with deteriorating air quality through 2054. The First Street Foundation’s latest research paints a grim picture of the future, spotlighting the alarming “climate penalty” our air quality faces due to an uptick in wildfires, heatwaves, and droughts predominantly in the West but affecting the nation unevenly.

At the heart of this study is an advanced, hyperlocal air quality model that peers into the future, from 2024 to 2054, to forecast shifts in air pollution down to the granularity of individual properties. Though the report itself hasn’t undergone peer review, it’s grounded in three peer-reviewed studies, offering a robust glimpse into a future where air quality gains of the past decades could be entirely wiped out.

The menace of particulate matter (PM2.5) and tropospheric ozone stands at the forefront of this looming crisis. PM2.5, a mix of tiny particles from various sources like vehicles, power plants, and wildfires poses a significant threat to human health, capable of infiltrating lungs and bloodstream alike, exacerbating or causing health issues. Tropospheric ozone, another villain in this tale, forms when pollutants from cars and industrial processes react in sunlight, further degrading the air we breathe.

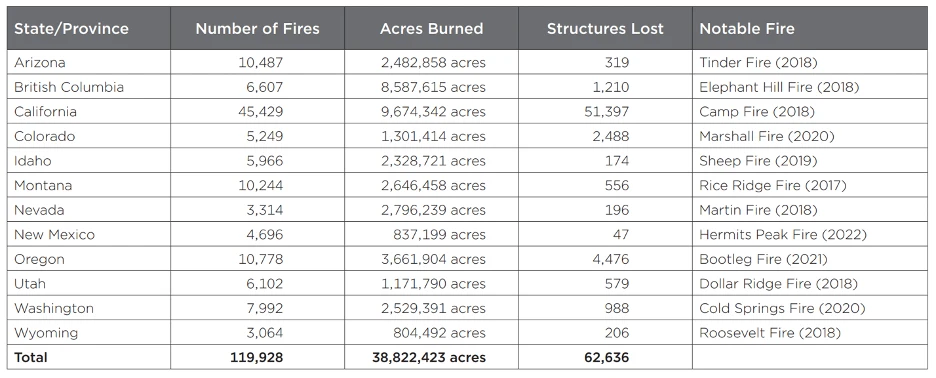

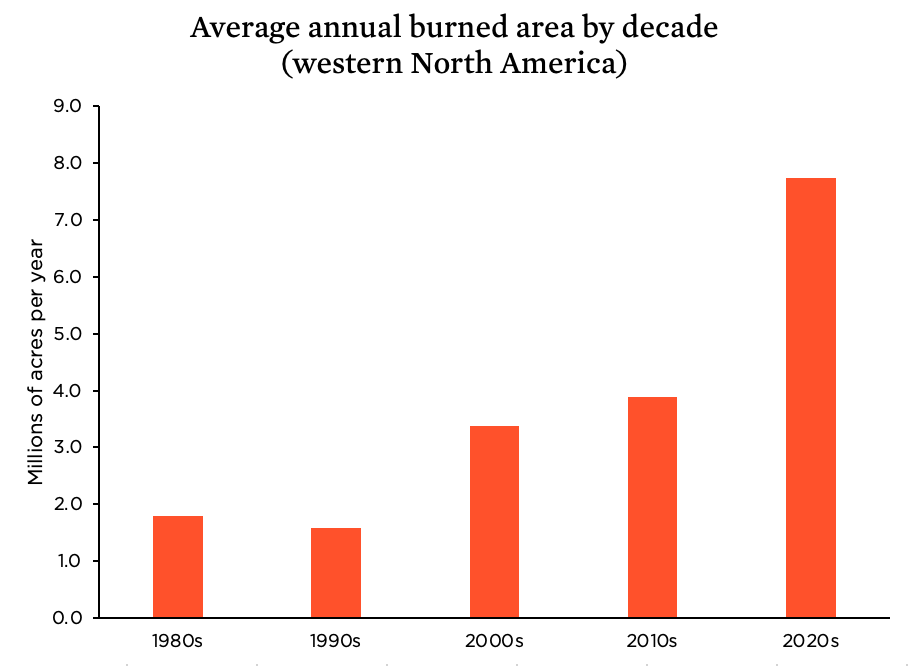

The West, according to First Street’s findings, is on the front lines of this battle against worsening air quality. Wildfires, becoming both more frequent and severe, are a primary source of PM2.5 emissions in the region.

California has seen a stark decrease in days marked “green” or “yellow” on the air quality index, replaced instead by a surge in more harmful air quality days. Since 2000, the state has witnessed a staggering increase in hazardous air quality days, surging by more than 1,100%. Across the West, the situation mirrors this distressing trend, with orange air quality days ballooning by as much as 477% between 2000 and 2021.

Cities like Fresno, Sacramento, San Francisco, and Seattle are emerging as hotspots for poor air quality, plagued by the dual threats of wildfire smoke and ozone pollution. Projections suggest a near 10% increase in PM2.5 levels over the next three decades, potentially erasing two decades of air quality improvements.

Jeremy Porter, head of climate implications at First Street, stressed the unparalleled challenge climate-induced air quality deterioration presents, far tougher to tackle than pollution from cars and factories due to its global nature.

The study forecasts a dire expansion in the population exposed to dangerous air quality levels, with those experiencing “hazardous” days on the air quality index expected to rise by 27% over the next 30 years. Over 125 million Americans could face at least one “unhealthy” air quality day annually within this timeframe, a stark increase from today’s figures.

Porter’s insights reveal a critical turning point: “The climate penalty, associated with the rapidly increasing levels of air pollution, is perhaps the clearest signal we’ve seen regarding the direct impact climate change is having on our environment.” This penalty not only underscores the immediate need for global emissions cuts but also highlights the intrinsic link between our climate actions and the air we breathe.

Looking ahead, the implications of First Street’s research extend beyond academia and policy, reaching into the lives of everyday Americans. The study’s findings are being translated into “Air Factor” ratings for individual properties, offering a tangible measure of air quality risks that will be accessible on major real estate listing sites.

More To Discover

- 1.5 Billion Tires Are Thrown Away Annually, A New Recycling Method Can Transform Them Into High-Value Products

- The Rise of Indoor Farming in Thailand Begins With Strawberries

- Combatting Microplastic Pollution: How You Can Make Your Laundry Routine More Sustainable

- UCLA and Singapore Launch Seawater Plant to Snatch 10 Tons of CO2 Daily, Produces Clean Hydrogen Fuel

This move not only democratizes access to crucial environmental data but also serves as a stark reminder of the pressing need for collective action against the backdrop of climate change. The fight for clean air, it seems, is far from over.

Sources: