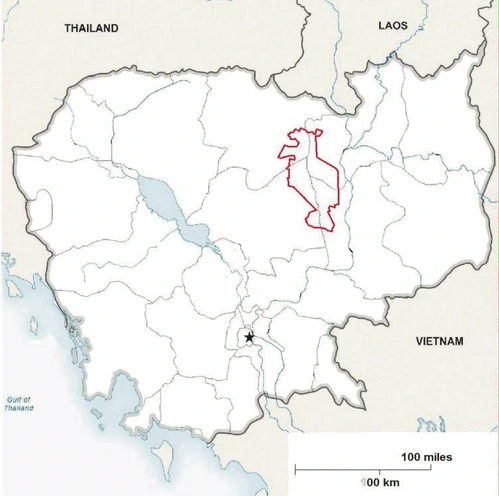

In the heart of Cambodia’s Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary, a story of environmental disregard unfolds, starring Late Cheng Mining Development—a Chinese company accused of illegal gold mining. This tale of greed begins years before the company even had a license to disrupt the peace of this ecological haven.

Awarded an exploratory license in March 2020 and an extraction license in September 2022, Late Cheng Mining Development has been a name whispered with dread among the locals of Snang An village. Villagers, speaking under pseudonyms like “Sopheap” to protect their identities, claim the company’s operations likely began as early as 2019, a whole year before any official paperwork was stamped.

The 37,300-acre gold mining operation has grown since then, encroaching upon the sanctuary that houses 55 threatened wildlife species and 80% of Cambodia’s endangered indigenous trees. The company’s activities, however, go beyond mere environmental encroachment.

The Poisoned Waters of Snang An

Residents of Snang An village, like “Sopheap”, live in fear and frustration. “The company operates as they please. We’ve asked the authorities for help, but they won’t do anything for us,” Sopheap lamented. The Bruno Manser Fonds report corroborates these claims, pointing out the risks of water contamination due to the company’s mining activities.

Ida Theilade, an ecologist and one of the report’s authors, highlights the dangers of open-pit mining. “The environmental threats are well known, including roads fragmenting a fragile rainforest ecosystem,” she said. These activities don’t just affect the land; they poison the lifeblood of the community—the Porong River.

The legality of Late Cheng’s operations is as murky as the waters they pollute.

According to the 2008 Protected Area Law, mining within protected areas like Prey Lang is strictly regulated, yet Late Cheng seems to operate with impunity.

Locals like “Sopheap” and “Dararith” (another villager) describe a chilling scenario where their voices are silenced by the company’s close ties with local authorities. The residents’ repeated pleas have fallen on deaf ears as they witness their once-pristine environment being decimated.

Late Cheng's Operations Are Destroying The Ecology Of The Sanctuary

Late Cheng Mining’s activities in Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary have raised significant ecological concerns. This sanctuary is not just an ordinary forest; it’s a biodiverse hotspot, critical for the survival of numerous endangered species. The mining operations threaten to disrupt the delicate ecological balance. The clearing of land for mining directly impacts the habitat of 55 threatened wildlife species. This includes rare and endangered birds, mammals, and reptiles, which rely on the dense forest cover for survival.

Moreover, the sanctuary is estimated to house 80% of Cambodia’s most endangered indigenous tree species. These trees aren’t only ecologically valuable but also culturally significant to the local communities. The loss of these trees would mean a loss of heritage and a critical carbon sink, crucial in the fight against climate change.

In the verdant expanse of Prey Lang, Late Cheng Mining Development’s use of hazardous chemicals like cyanide in gold extraction is horrifying. This method, known as cyanide leaching, is widely used in gold mining due to its effectiveness in extracting gold from ore. But, as you can imagine, the environmental and health impacts are extremely alarming.

Cyanide, a potent poison, poses a severe risk to aquatic life and the health of local communities. The locals have voiced concerns about the contamination of waterways, most notably the Porong River, which they rely on for their daily needs and sustenance.

In one stark instance, a mass die-off of fish in the river was blamed on the mining activities, although these claims couldn’t be independently verified primarily because neither the gold mining company nor the Cambodian government are willing to pay for testing.

The risks aren’t hypothetical. Independent laboratory tests of water samples, paid for by an NGO, from streams affected by the mining activities revealed the presence of cyanide, albeit below the allowable limit set by Cambodian and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency standards. Yet, these findings don’t discount the potential long-term impacts, especially considering the fluctuations in cyanide levels due to factors like heavy rainfall. And these tests were conducted well after the initial fish die-off, and the analysts were unable to test any of the actual dead fish.

Beyond the chemical hazards, the ecological costs of Late Cheng’s operations extend far beyond the immediate vicinity of the mines. The rerouting of streams for mining purposes not only disrupts the natural flow of water but also impacts the broader ecosystem. The alteration of waterways for mining interferes with the natural habitat of countless species and affects the soil quality and vegetation.

Furthermore, the mining operation has led to substantial deforestation within Prey Lang. This destruction isn’t only a loss of trees but also a loss of habitat for the sanctuary’s diverse fauna. While a logged forest can regenerate over time, areas ravaged by mining are often left barren, creating what ecologist Ida Theilade describes as “apocalyptic” landscapes.

The Political Web and Chinese Company’s Immunity

The political landscape surrounding Late Cheng’s operations reveals a complex web of influence and interests. The company’s board members, such as Zhao Yingming and Chun You, hint at connections reaching into the higher echelons of Cambodian politics and military. These connections suggest a possible reason for the apparent lack of government intervention in the face of legal and environmental violations.

Furthermore, the cozy relationship between Late Cheng and local authorities, as indicated by the company’s ease in circumventing regulations and the reports of donated cement to local police stations, paints a picture of a company operating with a degree of impunity. This scenario is not unique to Late Cheng; it reflects a broader issue within the region where economic interests often overshadow environmental and legal considerations.

In both cases, the underlying theme is the vulnerability of natural resources and local communities to the whims of powerful entities. Late Cheng’s operations in Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary exemplify the challenges faced in protecting ecological sanctuaries from exploitation, especially when political and economic interests are entangled.

The Chinese Connection and the Silent Suffering

The company’s board, featuring names like Zhao Yingming and Chun You, hints at a network of influence extending to the upper echelons of Cambodian politics. These connections have fortified Late Cheng’s operations, leaving the residents of Snang An in a state of despair.

“We asked them to stop because they were destroying the village,” Dararith said. “But all the site managers are Chinese, so when we try to communicate, they cannot understand us, and we don’t understand them.”

In the shadows of Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary’s fading glory lies a tale of geopolitical intrigue and local despair, emblematic of the larger narrative of Chinese investments in Southeast Asia. Late Cheng Mining Development, with its deep-rooted connections to Chinese business magnates and Cambodian elites, is a stark symbol of this expanding influence.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has been at the forefront of this expansion, bringing with it a wave of infrastructure and mining projects across Southeast Asia. While these projects promise economic development, they often come at a high environmental and social cost. In Cambodia, Chinese investments have skyrocketed over the past decade, with the mining sector being a significant recipient. These investments, while beneficial for economic growth, have raised concerns over environmental regulations and community rights.

More To Discover

- Sustainable or Not? The Controversy Over Gear Used in MSC-Certified Tuna Fishing

- New Beetle-Inspired Cooling Ceramic May Be the Game-Changer in Passive Cooling and Sustainability The Construction Industry Needs Right Now

- Wind Fence Innovates Clean Energy in Urban Landscapes

- Yellowstone Faces ‘Zombie Deer Disease’ Threat, Scientists Warn of Human Risk

A Community's Cry for Help Continues To Be Ignored

Late Cheng’s relentless pursuit of gold has left the community of Snang An in shambles. “There’s been no benefit to the community. Instead of benefits, the mine kills our livestock and pollutes our water,” Dararith adds. “We lost our land; it’s all company land now.”

In the face of such blatant environmental and human rights violations, the people of Snang An and the sanctuary they call home continue to suffer. The story of Prey Lang is a stark reminder of the consequences when greed and power override environmental stewardship and community well-being.