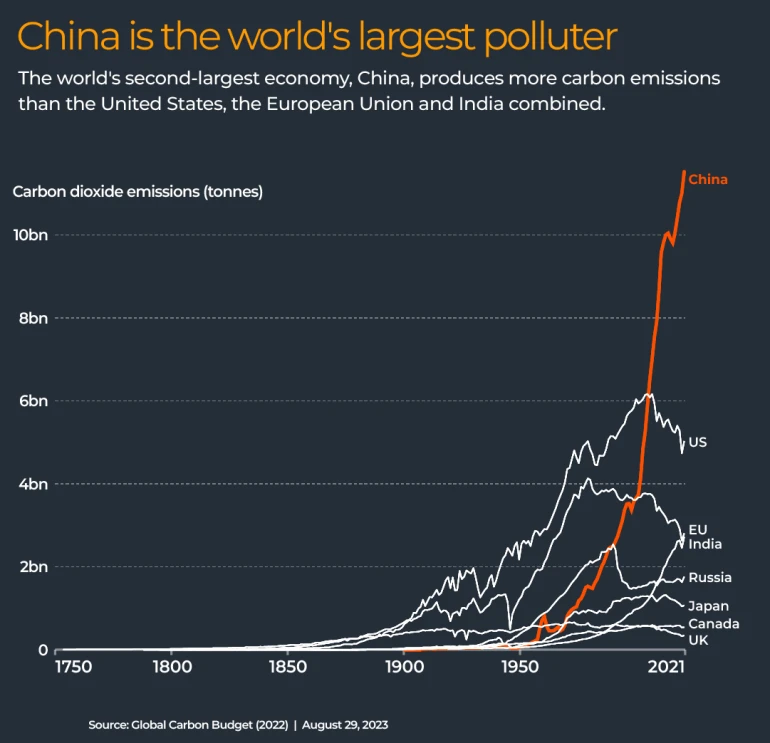

China’s bold promises of climate action have been overshadowed by a sobering reality: its emissions now exceed the combined emissions of the United States, the European Union, and India. This unsettling truth places a dark cloud over global efforts to combat climate change, and China, as the world’s second-largest economy, holds the power to either make or break these critical efforts.

While China has made strides in renewable energy, especially in solar power capacity, it grapples with surging emissions due to a relentless reliance on coal to fuel its cities and energy-intensive industries like steel production. In the second quarter of this year alone, Chinese emissions surged by 10 percent, putting the nation on track to surpass its previous record of 11.47 billion metric tons in 2021, according to data from Carbon Brief, a UK-based climate policy website.

Unchecked, this growing carbon footprint threatens to derail international climate mitigation efforts, which scientists already believe are falling far short of what’s needed to combat the dire consequences of rising temperatures. China’s economic dependence on coal is expected to persist, raising concerns that even if Beijing achieves its “peak carbon” goal by 2030, it may still be unacceptably high.

Furthermore, while China’s renewable energy ambitions are ambitious, they face significant hurdles, including an outdated power grid and the ongoing challenge of efficiently storing renewable energy.

The Tug of War

China’s dual role as a renewable energy leader and a coal consumption juggernaut paints a complex picture. Cory Combs, associate director of Trivium China, a policy research company, captures this duality, stating, “No one frankly comes close to China’s leadership in renewables, second place is quite distant. On the other hand, China is outpacing the rest of the world on coal as well.”

In 2020, Chinese President Xi Jinping pledged to reduce the nation’s emissions by 65 percent from their 2005 levels by 2030 and attain carbon neutrality by 2060. While these goals were reiterated in July, President Xi emphasized that energy policy would be driven by China’s needs and not “swayed by others.”

Energy Security Concerns

China’s recent surge in coal-fired power plant construction stems from concerns about future energy security. The nation has approved a staggering 86 gigawatts (GW) of new coal-fired plants in 2022 alone, green-lighting an additional 50GW in the first half of 2023, according to Greenpeace.

In total, China has a whopping 243 GW of new coal-fired power facilities in the pipeline, sufficient to power an entire Germany, as reported by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) and Global Energy Monitor.

Cory Combs highlights the central issue, explaining, “The biggest story right now is probably the energy security perspective. China will not give up coal until it has a guarantee of effective energy security. Specifically, we are looking at the ability to provide base-load power at any given time and the ability to guarantee it can meet any particular peak load.”

Beijing’s decision to double down on coal reflects a deep-seated fear of repeating energy crises that have plagued the industry in recent years.

Navigating Energy Challenges: China's Dilemma

In 2021, China faced a double whammy of energy crises.

Coal shortages, coupled with surging demand for goods during the COVID-19 pandemic, resulted in blackouts affecting 20 Chinese cities and provinces. The following summer, a drought triggered by an unprecedented heatwave reduced the capacity of the country’s hydropower dams, which constitute 16 percent of China’s power mix.

Confronted with this alarming sequence of events, provinces like Guangdong took matters into their own hands by bolstering their coal power capacity. Their aim was to prevent a recurrence of these issues, according to David Fishman, a senior project manager at the Lantau Group, an economic consultancy specializing in Asia-Pacific’s power and gas markets. Fishman suggests that someone in Guangdong’s energy planning office likely scrutinized the situation and decided to invest in additional backup capacity to safeguard against severe droughts in Yunnan.

China’s recent record-breaking emissions, in reality, may not fully reflect the country’s trajectory. Carbon-heavy industries like construction and steel were significantly disrupted due to lockdowns in major cities and manufacturing hubs. This disruption inadvertently contributed to a temporary reduction in emissions.

Despite these setbacks, some climate experts still believe that China can achieve “peak carbon” by 2030. However, the size of this peak remains subject to political considerations.

Boyang Jin, a senior carbon analyst at the UK-based LSEG, suggests that the new coal-fired power plants serve as a stopgap measure. Provincial governments will continue to be accountable for meeting climate targets set by the powerful National Development and Reform Commission.

Yet, amidst these aspirations, political risks loom large on the horizon.

In the following section, we’ll delve into the broader implications of China’s energy strategy, both for the nation and the world’s climate goals.

China's Carbon Crossroads: Communist Leadership Isn’t Backing Down

As China’s economy slows, there’s a looming possibility that Beijing may revert to its tried-and-tested formula of stimulating economic growth through construction and industry. This tendency has played out in the past and could, once again, influence the nation’s approach to emissions reduction. Furthermore, the powerful steel industry in China may resist efforts to curtail emissions, adding another layer of complexity to the climate challenge.

“The peak is in sight, it’s achievable, the preconditions are there, but there’s a risk for these two reasons that the peak gets delayed until very late in the decade, and that could single-handedly derail the global climate effort,” warns Lauri Myllyvirta, a lead analyst and co-founder of the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air.

China’s investments in renewables have been nothing short of remarkable. In 2022, Beijing led the world in clean energy investments, committing $546 billion, half of the global total for that year, as per BloombergNEF data. China’s current wind and solar capacity can meet approximately 30 percent of the nation’s energy needs, according to government figures.

However, translating these investments into reliable energy is a complex endeavor. Many wind and solar farms face a significant gap between their theoretical power generation capacity and practical usage.

One significant challenge lies in China’s limited capacity to store and transport power generated from renewables to areas with high demand. Despite 94 percent of China’s population residing east of the “Heihe-Tengchong Line,” which divides the country from northeast to southwest, many renewable energy sources, like hydropower dams and solar and wind farms, are situated in sparsely-populated western regions.

Other hurdles include government intervention in the energy market to artificially maintain low electricity prices, which can encourage excessive consumption.

More To Discover

Experts in the energy sector anticipate that China will continue to rely on coal for power generation for the foreseeable future. Achieving carbon neutrality by 2060, as pledged by China’s President Xi Jinping, hinges on the successful adoption of emerging technologies like carbon capture and green hydrogen over the coming decades.

David Fishman, a senior project manager at Lantau Group, remarks, “The real question is 2060, but obviously it’s far off. It relies on a lot of technologies that are far from being mature and scalable and cost-effective.”

Until those technologies are firmly in place, China’s dependence on coal is likely to persist, and it presents a daunting challenge to transition to cleaner energy sources.

In the end, as Cory Combs of Trivium China notes, “Coal is not necessary in principle, but there needs to be a lot more investment and there needs to be a lot of market reform in order to make that practical. And until they’re really in place, it’s coal. And so we get left in the status quo, where you have massive investments in renewables and continued investment in coal.”

As the world watches China’s delicate balancing act between economic growth and emissions reduction, the outcome will significantly influence global efforts to combat climate change.