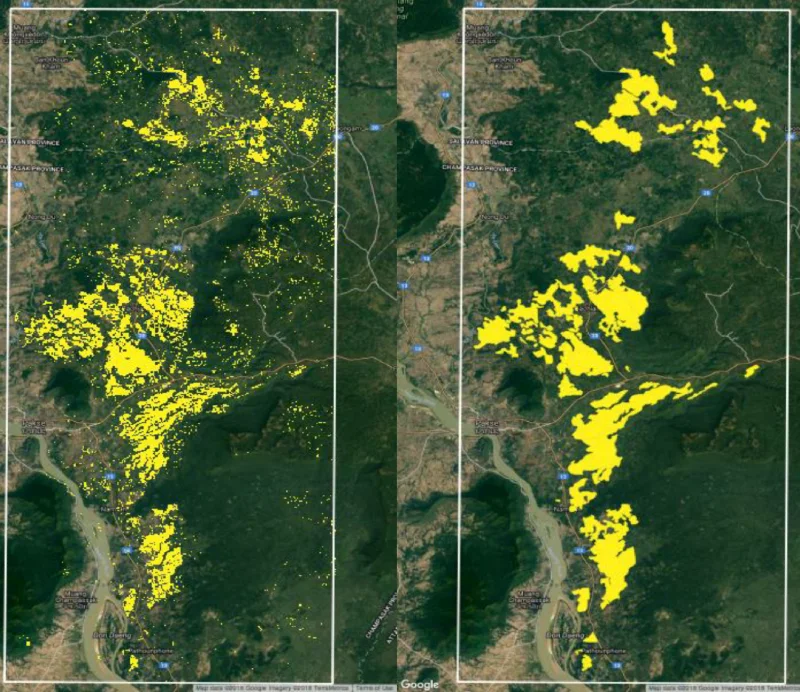

Annually, a staggering 1.5 billion tires are discarded worldwide, presenting both an environmental challenge and a missed opportunity in recycling. A recent study shed light on the immense environmental cost of natural rubber production, a key ingredient in tire manufacturing.

Since 1993, over 4 million hectares of Southeast Asian forests have been converted into rubber plantations, a rate of deforestation alarmingly two to three times higher than previous estimates.

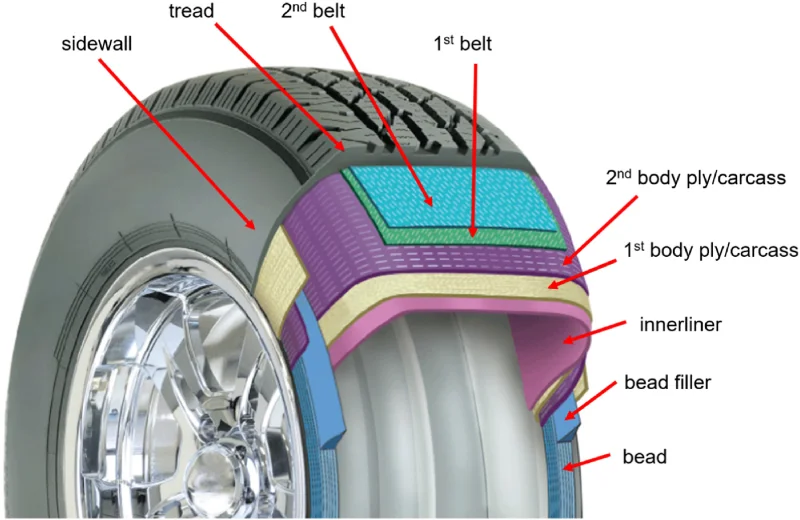

Natural rubber’s unmatched strength, wear-resistance, and flexibility make it indispensable in tire production, often blended with synthetic rubber to craft various tire components.

Imagine the environmental benefits if more of these tires were recycled: significant reductions in oil, energy, and forest consumption. Plus, recycling means fewer tires clogging up landfills or contributing to air pollution through incineration.

Yet, a 2021 paper revealed a concerning statistic: globally, less than 2% of rubber products are recycled or reused as rubber. The core issue lies in rubber’s resilience. Unlike many materials, rubber can’t be simply melted and reshaped. The vulcanization process, essential for creating durable tires, renders the material resistant to heat and chemicals, and subsequently tough to recycle.

However, there’s a silver lining. Researchers have developed a groundbreaking recycling process that could revolutionize how we handle used tires. This innovation offers a glimmer of hope, potentially shifting the tire industry towards more sustainable practices and significantly reducing the environmental footprint of rubber production.

Recycling Tires Is Actually Pretty Difficult

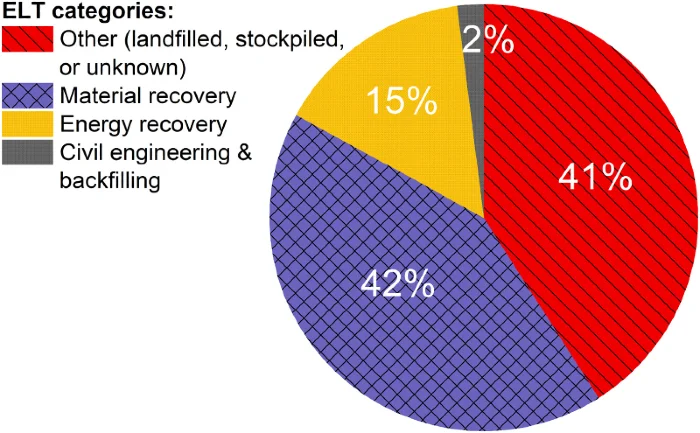

Addressing the rubber recycling dilemma is complex, primarily due to the material’s unique properties. When heated, rubber ignites and burns, releasing a significant amount of energy. Surprisingly, rubber contains more energy per gram than coal, making it a potent energy source. This high energy value is why most of Europe’s waste tires are incinerated for energy recovery.

However, burning rubber is far from ideal. This process only recovers about 37% of the energy embedded in the rubber. More concerning are the toxic fumes generated during combustion, posing environmental and health risks. Recycling rubber, in contrast, offers a more sustainable solution. It not only recovers more material value, but also curbs pollution significantly.

There’s a growing interest in rubber recycling technology. For instance, tire manufacturer Continental recently entered a partnership to source recycled rubber, claiming a massive 90% reduction in CO₂ emissions compared to using virgin rubber.

However, challenges remain. Typically, recycled rubber can only be used in concentrations up to 25% in new products before their quality diminishes.

Yet, there’s progress in this field. Researchers have developed a new material comprising 70% recycled rubber that retains the stiffness characteristic of natural rubber. Meaning, we may be looking at a promising future for rubber recycling!

This could potentially enable higher usage of recycled material while maintaining product integrity. Such advancements are crucial in transitioning from burning tires for energy to a more sustainable, circular economy approach in rubber usage.

Just How Do We Recycle Rubber?

Recycling rubber isn’t as straightforward as one might think. It’s a delicate process of breaking down the chemical bonds formed during curing, without damaging the core material.

To visualize this, imagine the tangled mess of cables behind your TV, but on a microscopic scale. In this analogy, each cable represents a polymer chain in the rubber. When you pull on a cable, it might snag on others but can generally be freed.

Curing essentially ‘clips’ these cables together, making it challenging to separate them without applying extra force. The key in recycling is to break these ‘clips’ without damaging the ‘cables.’ Fortunately, the clips are weaker than the cables, making targeted breakage possible.

Early attempts at recycling rubber in the 1980s were rudimentary and often broke both clips and cables, rendering the recycled material inferior to virgin rubber.

Consequently, recycled rubber, often in the form of ground tire rubber or “crumb rubber,” became relegated to low-value applications like filler for artificial turf – those pesky bits that invade your boots on older sports pitches.

The problem with this approach is that there’s already an ample supply of low-quality recycled rubber. The market needs higher-quality recycled rubber, suitable for making tires and seals – products with significantly higher global market value.

This wouldn’t only enhance the quality of recycled rubber products but could also drive a more robust worldwide recycling initiative for rubber.

At the University of Bradford, while collaborating with Sichuan University in China, the research team has made significant strides in recycling rubber. They’ve developed a technique that efficiently shears away the ‘clips’ while preserving the ‘cables.’

This process yields a kind of powder that closely resembles the properties of virgin rubber, thanks to the intact polymer chains.

This, in turn, opens the door to producing higher-quality recycled rubber, potentially reshaping the entire rubber recycling industry and paving the way for more sustainable rubber production and usage.

Is There A Circular Solution?

The future of rubber recycling hinges on a crucial shift: turning old tires into valuable resources. Right now, the complex mix in tires – synthetic and natural rubber, fillers, and chemicals – makes recycling tough. It’s hard to separate and identify different rubber types, just like with plastics. In China, for example, recycled rubber is often contaminated with a mix of rubber types and metal.

Tire companies are aiming to use more recycled rubber, but it’s a tricky balance. They need to mix recycled and new rubber without losing quality. Understanding how rubber changes during recycling is key. This knowledge could convince more manufacturers to use recycled rubber, transforming old tires from costly waste to a valuable resource.

If recycled tires become part of high-value products, it would change the game. We’d see less illegal tire dumping and toxic fires. Also, developing countries wouldn’t be burdened with our waste tires, often burned there.

More To Discover

- Musk Lied About Using Terminally Ill Monkeys at Neuralink; They Died Horribly

- It’s Alive! How New Living Materials are Transforming Architecture

- UC Davis Scientists Use Volcanic Rock to Capture Carbon in Dry Climates, Offering New Hope for Climate Action

- Lab-Grown Oil: The Next Frontier in Sustainable Food Production?

Investment and innovation can make this circular economy a reality, turning the 1.5 billion tires wasted each year into something useful again.