Here’s a shocking statistic you can share with friends, the banana is Walmart’s number one selling item. That’s right. Not potato chips and not even Pepsi.

In fact, bananas appear to be so perfect for human consumption that Kirk Cameron once tried to use the simple banana in an attempt to prove the existence of God.

But Kirk had a problem, one of science, actually. You see, the grocery store banana he held up for the world as proof, were actually created by people.

Of course, there are still wild bananas throughout South America and Southeast Asia, where they’re native.

In fact, there are dozens of species and thousands of varieties, but they’re not the ones we eat. They aren’t the iconic Chiquita banana we all know and can easily identify.

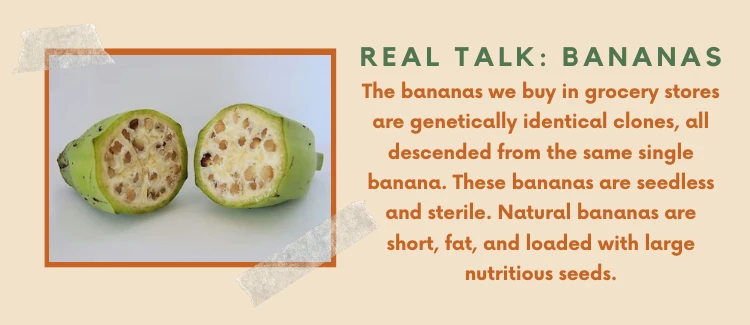

Many of those species, as you might suspect, have seeds. After all, that’s what makes them fruit – fleshy bodies containing seeds. Have you asked yourself why have you never eaten a banana seed? You have, and you haven’t, depending on your perspective.

Cultivated bananas from the store have no seeds, but now and then, if you look closely, you’ll see tiny black specs. Those are what is left of the original seed.

And before you ask, they’re not fertile, meaning you can plant them and take great care of them and nothing will grow.

Technically, today’s bananas are sterile mutants. I’m not trying to shock you, that’s just the truth.

Now, unless you were buying bananas in the late 1950s, every banana you have ever eaten is genetically identical.

Our store-bought bananas are known as Cavendish, a virtually seedless variety that has never appeared in nature. How could it? It can’t reproduce.

Before the popularity and mass production of the Cavendish banana, everyone was still eating the same type of banana, but this wasn’t unheard of.

In actually, it wasn’t even new.

The original mass available banana was known as the Gros Michel. It was bigger and sweeter with a thicker skin.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t immune to a fungicide resistant pathogen called the Panama disease.

By the time growers worldwide communicated with one another and understood the danger their Gros Michel crops faced, it was too late.

The disease had spread and in less than two years the Gros Michel was all but extinct. The Gros Michel banana simply did not have the genetic variations to build up immunities to the disease.

The entire cultivated banana industry collapsed, but thankfully not for long. Enter the Cavendish! This banana was created by fusing together several other types of bananas until the highly preferred fruit was created.

No seeds to deal with, which also ensured consumers couldn’t grow their own. It was less sweet, which meant it contained less fructose and so held a longer shelf life.

And the skin was thinner and easier to simply slip down when one was hungry. The Cavendish saved the banana industry and, in doing so, thousands of jobs at the time.

Of course, since they’re seedless the only way to reproduce them is to transplant part of the plant stem and that is exactly how it’s been done for the last 50+ years.

Thanks to the unique and multifaceted genetic makeup of the Cavendish, the fruit is resistant to the Panama disease.

And it is because of this moment in agricultural history that the world collectively switched from one banana to another.

But this brings us to a potentially larger problem and one that proves humanity does not always learn from our own history.

You Have Tasted The Gros Michel Banana, You Just Didn't Know It

Have you noticed that when you eat a banana flavored product, it doesn't taste like our banana? The banana flavoring that's used in puddings, extracts, drinks and much more have a strong, vibrant, and defined banana taste. There's a reason for this. Cavendish bananas aren't used to provide flavorings. Those natural banana flavors actually come from the much older, and long forgotten, Gros Michel banana. While few Americans have ever tasted the once popular Gros Michel banana before the disease all but wiped them out, all Americans can recognize the taste. Thanks to the Gros Michel banana's potency, size, and higher sugar content, they make perfect concentrated flavorings. Solely for the extract industry a few crops of Gros Michel bananas are grown, primarily in Jamaica, with processing on-site to prevent any potential cross-contamination should the panama disease reach them again.

Is history destined to repeat itself?

The Gros Michel banana was genetically identical, and it was due to this genetic monotony that the fruit succumbed so quickly to the pathogen.

And as all bananas were Gros Michel, all genetically identical, the disease infected a single fruit and spread rapidly.

To save ourselves from the weakness of a single genetic crop, we merely replaced it with another.

While the Cavendish was capable of defeating the Panama disease 60 years ago, the disease has had time to mutate and adjust, while the banana has remained exactly as it was in the early 1960s.

In fact, the banana you purchase at the store today in 2022 is genetically the same banana that was consumed in 1965.

What a terrifying reality, if you like bananas. Before you jump to the conclusion that the strain hasn’t mutated or has died out completely, take a beat and prepare yourself (and your banana pudding recipe).

A mutated form of the Panama disease that does affect the Cavendish banana has already been identified.

Thankfully it was quickly contained, but that will likely not always be the case.

After all, a global monoculture of genetically identical individuals is a beautiful sight to a pathogen.

The fungus must only infect and destroy a single individual, and suddenly there’s no diversity to stop it or even slow it down.

This has led to many scientists predicting the outright demise of the Cavendish, as was the fate of its predecessor six decades ago.

The good news is that large agricultural companies and a handful of well-known universities are attempting to get ahead of the problem.

More To Discover

- 10 Foods That Originally Looked Totally Different Until We Changed Them

- 9 Most Bizarre Genetically Modified Plants Ever: When Science & Nature Work Together

- Scientists Breed Climate-Friendly Cows with 20-Fold Increase in Milk Production

- Snapdragon DNA Meets Tomato: Grow a Super Healthy Purple Marvel in Your Garden

They’re trying to ensure that history doesn’t repeat itself by taking steps to protect the Cavendish.

Some growers are creating genetically different bananas that might replace the Cavendish crop if it fails. Think of it as a backup banana.

While some scientists are attempting to genetically engineer Cavendish plants with immunity to the dreaded Panama disease and its mutations and known variants.

The world has a whole and particularly the scientific community learned a lot from The Grove Gros Michele debacle. They watched it infect fields and quickly destroy them, while the growers were helpless to stop the plant massacre.

They know the likelihood of a newer, stronger and more vicious strain of the panama disease is high, and they know the Cavendish simply isn’t diverse enough to withstand it.

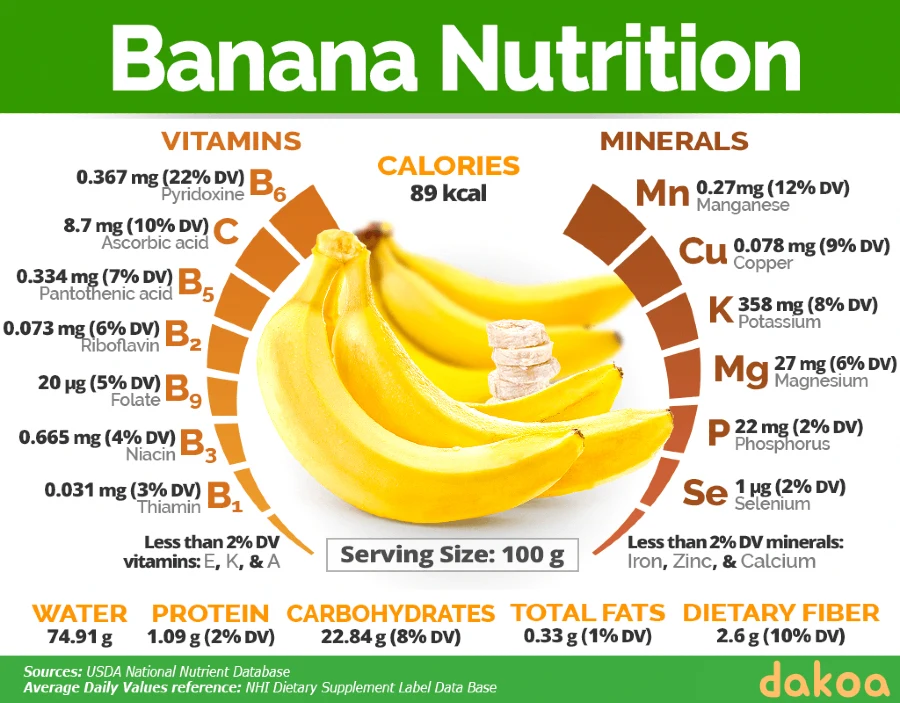

I personally am grateful for the agribusinesses, growers around the world, and our agricultural scientists who are working tirelessly with absolutely no recognition to ensure the global supply of this nutritious fruit.

Perhaps if our ancestors had the resources and knowledge we have now, we wouldn’t be missing out on these six, now extinct foods.

And to continue providing it inexpensively, so all may enjoy.