The Midwest landscape is dominated by vast expanses of corn and soybeans, but amidst this monoculture, one farmer in central Missouri is breaking the mold.

Linus Rothermich has been growing Japanese millet since 1993, and it’s proving to be a game-changer.

Seeking alternative crops to improve profitability, Rothermich turned to Japanese millet. Compared to his corn and soybean crops, Japanese millet requires significantly less investment. Its shorter growing season seamlessly fits into his crop rotation.

Delighted with the results, Rothermich jokingly admits to keeping the grain to himself, fearing a drop in prices if other farmers catch on.

The year 2023 has been declared the International Year of Millets by the United Nations, shedding light on these humble grains.

Millets are highly sustainable, resilient to adverse weather conditions, and offer excellent nutrition, making them a valuable addition to the global food system.

Despite their remarkable qualities, millets have received considerably less policy and research attention in the United States compared to crops like corn and soybeans.

Makiko Taguchi, an agricultural officer at the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, notes that millets have been neglected and marginalized, lacking the investment and research resources bestowed upon major crops like maize, wheat, and rice.

However, millets hold tremendous potential to contribute to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, and the International Year of Millets aims to rectify the oversight, similar to the success of the International Year of Quinoa in 2013.

Millets come in various forms, including pearl millet, foxtail millet, proso millet, and more. Sorghum can also be considered a type of millet. These grains require less fertilizer and exhibit greater resistance to insects and diseases.

Moreover, farmers can use existing equipment for millet cultivation, simplifying the transition.

While millets may not currently match the yields of commodity crops, farmers like Rothermich believe the advantages outweigh the trade-offs.

Drought resistance is a critical characteristic of many millet varieties, making them particularly valuable in regions affected by water scarcity, such as the Midwest and Great Plains.

Matt Little, a farmer from Oklahoma, was amazed by proso millet’s ability to withstand extreme heat and drought conditions while still producing a profitable harvest.

Millets have also captured the attention of the University of Missouri’s Center for Regenerative Agriculture, which provides valuable information to farmers interested in incorporating these grains into their practices.

Rob Myers, the center’s director, highlights the versatility of millets. Proso and pearl millet thrive in drier states like Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas, where concerns about water supply are prevalent.

Japanese millet, on the other hand, excels in hot and humid conditions and is often used to support wildlife in creek bottoms.

Although the market for millets is currently limited in the United States, they have potential applications as songbird seed, livestock feed, cover crops, and even biofuels.

As the demand for gluten-free alternatives continues to rise, millets could emerge as a popular food choice.

Rob Myers expects incremental market opportunities for millets, driven by evolving consumer preferences.

However, the lack of federal protection and support hampers millets’ progress.

Unlike cash crops like corn and soybeans, millets do not enjoy the same level of insurance coverage, market prices, and commodity grant support.

Consequently, securing research grants for millet-related projects is challenging. Ram Perumal, the head of Kansas State University’s millet breeding program, believes increased recognition of millet science through the UN Year of Millets could address this disparity.

More To Discover

- Easy Food Swaps Could Slash Household Grocery Emissions by 26%

- 2023 Saw 356,000 Heat Pumps Installed In Germany: 50% Surge in Installations for Second Year Running

- Heartworms and UV Hazards: Climate Change’s Toll on Pets and Polar Wildlife

- Researchers Craft Sustainable Bioplastic Pellets From Eggshells to Replace Plastic

Further research is essential to unlock the full potential of millets. Rob Myers emphasizes that a million-dollar investment in millet research could yield significant advancements, unlike a similar investment in corn research.

For example, improving millet yields is a more achievable goal than reducing corn’s water requirements, according to James Schnable, a professor at the University of Nebraska.

To bridge the funding gap, James and Patrick Schnable co-founded Dryland Genetics, a start-up dedicated to researching and breeding proso millet varieties.

Jeff Taylor, a farmer from Iowa, began cultivating proso millet six years ago with the support of Dryland Genetics. He believes that increased research and incentives are necessary to encourage farmers to explore alternative crops beyond the traditional corn and soybeans.

Taylor envisions a future where crops like proso millet receive more attention, allowing farmers to diversify their operations.

In conclusion, millets possess remarkable qualities that make them ideal for sustainable and climate-resilient agriculture.

As the International Year of Millets gains momentum, there is hope that these ancient grains will receive the recognition, investment, and research they deserve, fostering a more diverse and resilient food system.

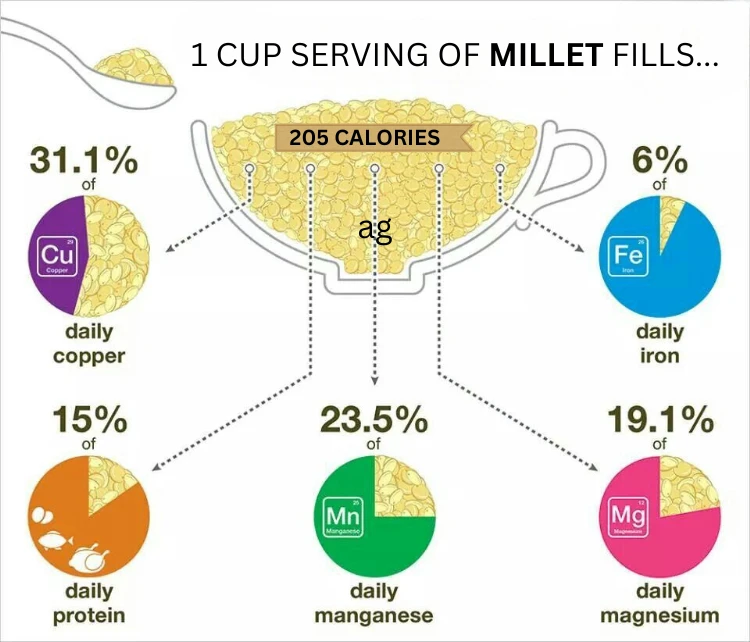

Still on the fence about millet, here’s a quick list of the nutritional benefits that may change your mind:

- High in dietary fiber, supporting healthy digestion and promoting satiety.

- Rich in essential minerals like iron, magnesium, phosphorus, and potassium.

- Contains a good amount of protein, making it a valuable source of plant-based protein.

- Gluten-free, making millet a suitable option for individuals with gluten sensitivities or celiac disease.

- Provides antioxidants that help combat oxidative stress and inflammation in the body.

- Low glycemic index, contributing to better blood sugar control and reducing the risk of diabetes.

- Contains beneficial plant compounds like polyphenols and lignans, which have antioxidant and anti-cancer properties.

- Good source of B vitamins, including niacin, thiamine, and riboflavin, which are essential for energy production and brain function.

- Offers a balance of complex carbohydrates, supporting sustained energy release and preventing blood sugar spikes.