Permaculture is more than just a gardening technique; it’s a comprehensive design system for creating sustainable and productive human habitats. It emphasizes working with nature, not against it, to build resilient ecosystems that meet our needs for food, water, shelter, and community. This article will delve deep into the world of permaculture, exploring its history, core principles, practical applications, and real-life examples that showcase its transformative power.

A New Approach: The History of Permaculture

Permaculture emerged in the late 1970s as a response to the environmental degradation caused by industrialized agriculture. Environmental psychology professor Bill Mollison and ecologist David Holmgren, the co-founders of permaculture, envisioned a system that mimicked the interconnectedness and efficiency of natural ecosystems. Originally the men coined “permaculture” from “permanent agriculture” but later expanded its meaning to the broader, and more inclusive, “permanent culture”. They saw conventional agriculture, with its reliance on chemical fertilizers and monoculture farming, as unsustainable and damaging to the land.

Permaculture borrowed inspiration from traditional agricultural practices around the world. Ancient techniques like swales (ditches that collect water) and guild planting (planting companion species together for mutual benefit) found a new home in the permaculture design system. Permaculture wasn’t simply a revival of old methods; it was about adapting them to the challenges of the modern world.

But, even though the term itself wasn’t cointed until 1978, sustainable land practices have been around for some time. In fact, a few of these historical examples included our modern understanding of sustainable land management practices.

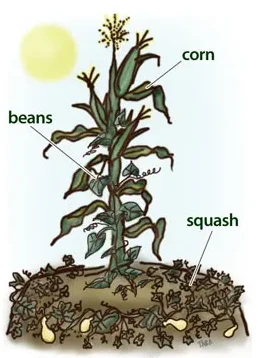

- Three Sisters Agriculture: Indigenous North American tribes planted corn, beans, and squash together. The corn stalks provided support for the climbing beans, while the beans fixed nitrogen in the soil to benefit all three plants. The squash sprawled on the ground, suppressing weeds and retaining moisture.

- Inca Terraces: The Incas in South America built terraces into mountainsides to create fertile land for agriculture. These terraces minimized erosion and maximized the use of scarce arable land.

- Forest Gardens: For centuries, cultures around the world have cultivated diverse and productive forest gardens. These multi-layered systems integrate trees, shrubs, herbs, and vines, mimicking the natural structure of a forest and providing a continuous harvest of food and other useful products.

The Core Principles of Permaculture

Permaculture rests on a set of core ethics and design principles that help guide decision-making and practical action:

The Ethics

- Care for the Earth: Everything in nature is interconnected. We have a responsibility to protect and regenerate our ecosystems, ensuring that resources are used sustainably and the health of the planet is prioritized.

- Care for People: Sustainable societies are built on mutual support, ensuring that everyone has access to the resources and knowledge needed to thrive. Permaculture encourages fair economic systems, resource sharing, and community-focused decision-making.

- Fair Share (Setting Limits and Redistributing Surplus): Permaculture takes a global view, recognizing the needs of both human and non-human life. It advocates for responsible consumption and using surpluses to expand and replicate sustainable systems.

The Design Principles

- Observe and Interact: Before taking action, it’s crucial to deeply observe a site: its existing ecosystems, weather patterns, and unique characteristics. This information becomes the foundation for your design.

- Catch and Store Energy: Identify ways to capture and make use of available resources, like rainwater, sunlight, and organic waste products.

- Obtain a Yield: Ensure your designs result in something useful: food, building materials, healthy soil, biodiversity, or other valuable outcomes.

- Apply Self-Regulation and Accept Feedback: Be responsive to changes and adjust the system along the way. Continuous learning and adaptation are key.

- Use and Value Renewable Resources and Services: Rely on what nature provides whenever possible, rather than relying on non-renewable resources.

- Produce No Waste: Aim to design systems where every “waste” product becomes a resource in another part of the system.

- Design from Patterns to Details: Start with the big picture – understanding overall patterns and relationships – before planning specific details.

- Integrate Rather Than Segregate: Aim for elements within your design to support and enhance each other.

- Use Small and Slow Solutions: Start with manageable interventions to observe results and iterate, rather than large, disruptive changes.

- Use and Value Diversity: Diverse ecosystems are more stable and resilient. Seek to mimic this diversity in your permaculture designs.

- Use Edges and Value the Marginal: The edge zones between different ecosystems are often the most dynamic and productive. Look to incorporate these transitions into your designs.

- Creatively Use and Respond to Change: Change is inevitable, so permaculture designs embrace it, viewing it as an opportunity for improvement.

Understanding these foundational concepts is key to designing effective permaculture systems. And now that you know them, let’s move on to the practical aspects of permaculture.

Permaculture in Practice: Beyond Gardening

While often associated with food production, permaculture extends far beyond just growing your own vegetables. Let’s dive into specific areas where permaculture design can be applied:

Food Systems

- Food Forests: These multi-layered systems mimic natural forests, with fruit and nut trees as the canopy, shrubs, and berry bushes underneath, and herbs and vegetables on the ground. Food forests are self-regulating, require minimal input, and provide a steady yield.

- Integrated Animal Systems: Chickens, ducks, goats, and other animals can play vital roles in permaculture. They can help with pest control, soil fertility, weed management, and provide produce like eggs, meat and milk.

- Keyhole Gardens: Circular raised beds with a compost basket in the center, ideal for small spaces and maximizing efficiency.

- Aquaponics: Combining fish farming with hydroponics to create a closed-loop system where fish waste fertilizes plants and the plants clean the water.

Water Management

- Rainwater Harvesting: Collecting rainwater in swales, ponds, barrels, or underground cisterns provides long-term water storage for irrigation and other uses.

- Swales: Ditches on contour (level with the land) that slow down water flow, allowing it to infiltrate the soil and increase moisture retention.

- Greywater Systems: Safely reusing water from showers and sinks for irrigation. Some even go so far as to integrate a composting or incinerating toilet.

Shelter and Energy

- Natural Building: Using materials like cob, straw bales, or earthbags to construct energy-efficient and environmentally friendly structures.

- Passive Solar Design: Building homes to maximize natural heating and cooling to reduce dependence on bought-in energy sources.

- Renewable Energy Systems: Incorporating solar panels, wind turbines, or micro-hydro systems to produce clean energy on-site.

Community and Economics

- Community Gardens: Shared spaces where people work together to grow food and build relationships.

- Community Supported Agriculture (CSA): A model where people subscribe to a farm and receive regular shares of the harvest. This offers farmers secure income and consumers fresh, local food.

- Local Exchange Systems: Networks for bartering goods and services, fostering a resilient and less-reliant local economy.

Real-Life Examples

- Zaytuna Farm, Australia: A large-scale permaculture farm that incorporates regenerative grazing, water retention strategies, and extensive food forests.

- Mark Shepard’s New Forest Farm, Wisconsin: Focused on perennial staple crops like chestnuts and hazelnuts, demonstrating how permaculture can provide a commercially viable alternative to intensive annual crop production.

- Detroit Food Commons, USA: An urban project addressing food insecurity and social disconnection through community gardens, orchards, and educational programs.

These show how permaculture moves from concept to action, creating tangible solutions to real-world problems.

Now, let’s get into how you start designing your own permaculture system, whether it’s a small backyard or a larger piece of land…

The Permaculture Design Process

While there’s no single rigid approach to permaculture design, here’s a general outline of the process:

- Observation and Site Analysis:

- Start by carefully watching your site. What are the patterns of sun, shade, and wind? Where does the water flow? What existing plants and animals are present?

- Analyze your soil type, topography, and existing infrastructure.

- Identify your needs and goals. Do you want to grow food, create a wildlife haven, or build a more sustainable home?

- Zones and Sectors:

- Zones: Divide your site into zones based on frequency of use and interaction. Closer to home are intensively managed areas (e.g., vegetable garden), while further out are less intensively managed zones (e.g., woodland).

- Sectors Consider external influences like prevailing winds, sun angles, potential wildfire risks, or views you want to enhance or block.

- Element Placement and Design:

- Position elements based on their needs, functions, and how they can support each other. For example, plant a vegetable garden in a sunny location near a water source, with compost production nearby.

- Use principles like “each element performs multiple functions” and “each important function is supported by multiple elements.”

- Pathways and Connections:

- Design efficient pathways between elements for movement and maintenance.

- Think about how energy and resources will flow through your system.

- Implementation and Refinement:

- Start small! Permaculture evolves over time. Implement elements in phases, observing how they work and making adjustments.

- Be flexible and learn from your successes and failures.

Tools and Techniques

Permaculture design uses various tools and techniques to help with the process:

- Scale of Permanence: A framework to organize design decisions based on how easily things can change, from climate (difficult to alter) to soil (easier to modify).

- Maps and Site Plans: Creating sketches, 3D models, or detailed maps is a great way to visualize your design and aid planning.

- Plant Guilds: Grouping plants with complementary functions (e.g., nitrogen fixers, pest repellents, and food crops).

Getting Started

- Find a Mentor or Course: Consider taking a permaculture course or connecting with a local permaculture designer for guidance.

- Visit Permaculture Sites: Inspiration is key! Seek out local farms, homesteads, or community projects that use permaculture.

- Read and Research: There are many great books and online resources available to expand your knowledge on permaculture.

Additional Tips

- Don’t Be Afraid to Experiment: Adapt techniques to your unique circumstances.

- Focus on Diversity: A variety of crops, animals, and elements promote resilience within your system.

- Document Your Progress: Take photos, keep a journal, and track your observations to help you adjust and improve your design over time.

Designing a permaculture system is a rewarding journey – a continuous learning process that empowers you to create a more sustainable and self-sufficient lifestyle.