Shark finning, the brutal practice of cutting off a shark’s fin and discarding the rest of the animal, has become a global symbol of unsustainable fishing. Despite being incredibly cruel and wasteful—95% of the shark is thrown away—this method has been primarily used to supply fins for expensive soups.

The outrage against this practice has been loud, with documentaries exposing the dark side of the trade and campaigns collecting hundreds of thousands of signatures demanding an end to shark finning. Governments worldwide have responded with bans, aiming to curb this practice.

At first glance, these efforts seem to be making a difference, but a closer look reveals a troubling trend: shark populations may still be in peril.

A recent study published in Science delves into the impact of these finning bans, analyzing shark catch data from 150 countries and international waters from 2012 to 2019. Darcy Bradley, a co-author and scientist with the Nature Conservancy in California, points out a startling finding: “Despite myriad regulations intended to curb shark overfishing, the total number of sharks being killed by fisheries each year is not decreasing. If anything, it’s slightly increasing.”

So, what’s going on?

The Unintended Consequences of Finning Bans

The study observed that global legislation against shark finning grew tenfold over seven years. Countries like Brazil, Taiwan, and Venezuela required fishers to land sharks whole, a move aimed at discouraging finning. Fiji even imposed a total ban on shark fishing. However, these well-meaning regulations have led to an estimated 4% increase in shark deaths in coastal fisheries, translating to 76-80 million more sharks killed annually, mostly within national jurisdictions.

Lead author Boris Worm from Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia explains, “Widespread legislation designed to prevent shark finning was successful in addressing this wasteful practice but did not reduce mortality overall.” The study, after consulting nearly two dozen experts, found that bans led to fishers retaining the entire shark, creating new markets for shark meat, oil, and other products in countries previously uninvolved in shark consumption.

Nidhi D’Costa, another researcher from Dalhousie University, emphasizes the lack of community-level initiatives in past conservation efforts. She highlights the importance of such efforts, especially where small-scale fisheries, significantly contribute to shark mortality.

A Global Perspective on Shark Mortality

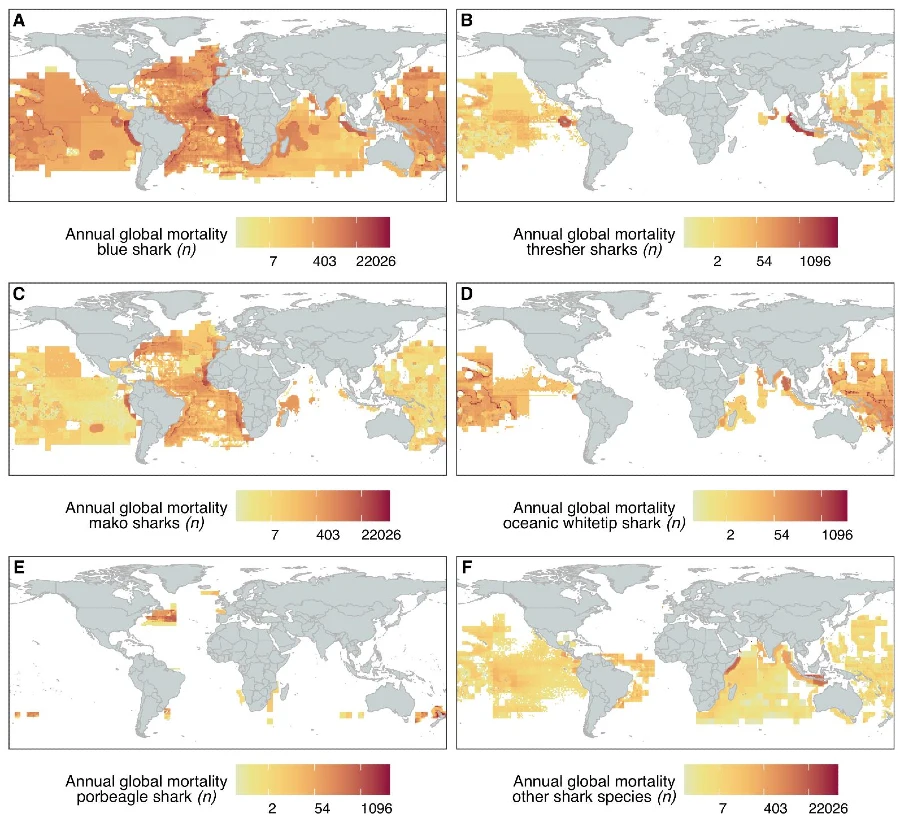

Shark deaths aren’t evenly distributed worldwide. Tropical countries like Indonesia, Brazil, Mauritania, and Mexico see higher shark mortality rates due to lenient fishing regulations. Conversely, the study notes some success in open-ocean fisheries managed by tuna regional fisheries management organizations, where retention bans and strict measures have reduced shark deaths by about 7%, particularly in the Atlantic and western Pacific.

This research underscores the complexity of shark conservation, showing that while bans on finning are a step in the right direction, they inadvertently might lead to higher overall shark deaths. Effective shark conservation requires a comprehensive approach, combining strong governance with innovative solutions to ensure these majestic creatures’ survival.

More To Discover

- Study Shows Killing ‘Outsider’ Animals May Hurt, Not Help, Nature

- They’re Using Dirt To Power Fuel Cells! Soil-Based Microbial Fuel Cells Offer Nearly Limitless Energy

- The UK Has A Biomass Problem: Sustainability Questions Threaten Green Energy Goals In Biomass Industry

- The Sweet Smell of Pest Control: Roses to the Rescue in Organic Farming

The call to action is clear: support nations struggling with shark conservation and think creatively to protect sharks. As the research team stresses, time is of the essence in safeguarding these vital ocean inhabitants from the brink of disaster.

Source: Science