In 1995, a band of eminent scientists, under the United Nations, sounded an alarming bell: human activities were heating up our planet, and the consequences would be dire and, crucially, irreversible. Fast-forward to today, in what’s been declared the hottest year in 125,000 years, and we find ourselves navigating a perplexing landscape where #climatescam hashtags garner more traction than those screaming climate emergency.

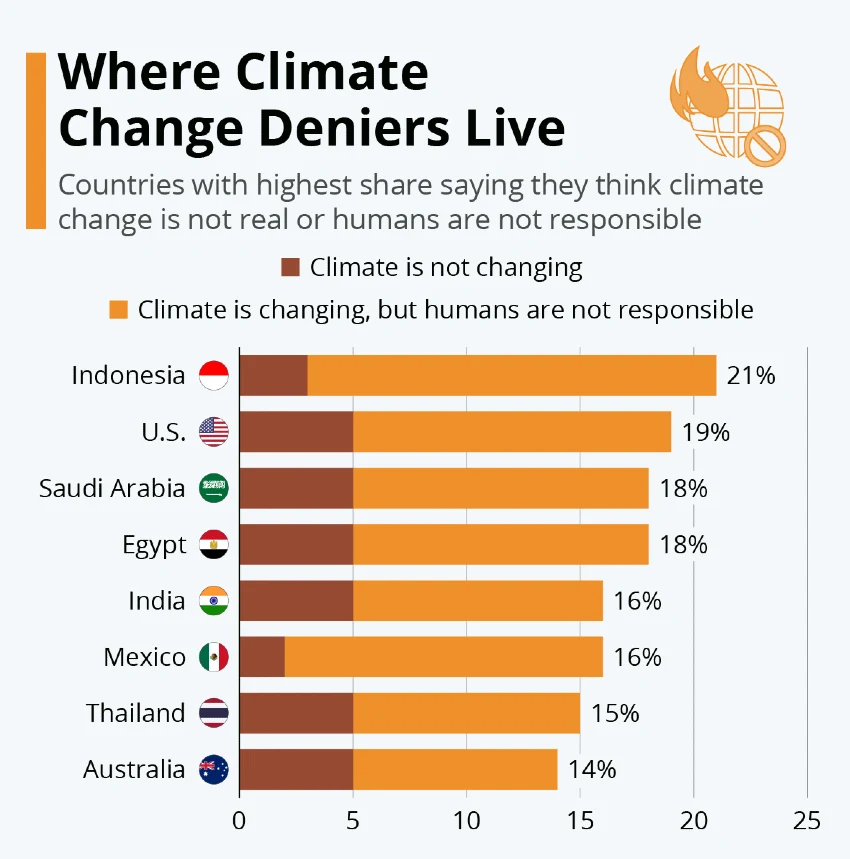

It’s staggering, isn’t it? Peering out your window, witnessing the untimely blooming of flowers, or the delayed freezing of lakes, yet 15% of Americans still cling to the fallacy that global warming is a farce. It begs the question: what fuels this persistent denial in the face of glaring truths?

Enter Andy Norman, philosopher, and co-founder of the Mental Immunity Project. He argues that our psychological makeup can lead us astray, luring us into a false sense of security as we cherry-pick facts to bolster pre-existing beliefs. “The more you rely on useful beliefs at the expense of true beliefs, the more unhinged your thinking becomes,” Norman elucidates. And therein lies a part of the conundrum – these climate change denials aren’t just innocuous opinions; they’re a collective delusion, a refusal to confront the unsettling reality.

The allure of conspiracy theories adds another layer. They offer an intoxicating blend of secrecy and revelation, making their believers feel like they’re privy to some grand truth hidden from the masses. Think of the Flat Earthers, convinced they’re glimpsing beyond the veil that blinds the rest.

With each United Nations climate summit, there’s an uptick in misleading social media content. The recent COP28 was no exception. False claims about government land seizures and intentional food shortages flooded online spaces, undermining efforts to address climate change and even inciting harassment of climate scientists.

The real kicker? A study in Nature Human Behavior found that climate change disinformation is more persuasive than cold, hard scientific facts. Researchers at the University of Geneva threw nearly 7,000 people from diverse countries into a storm of real tweets promoting climate change myths.

The outcome was disheartening – exposure to these tweets swayed people’s belief in climate change, dampened their support for emission-reducing actions, and eroded their personal commitment to change.

Only prompts urging participants to evaluate the accuracy of information they encountered seemed to anchor them back to reality.

This phenomenon speaks to the heart of why disinformation is so potent: it preys on emotions, stoking anger and fear. It’s easier to rail against elites conspiring to make you eat bugs than to confront the scientific consensus on climate change.

So, what’s the antidote? According to Norman, the key might lie in “inoculation” – exposing people to a diluted form of disinformation to build resistance. This approach, akin to a vaccine, helps individuals understand the motives behind falsehoods.

A prime example was the Biden administration preemptively countering Russia’s false narratives during the Ukraine crisis, significantly blunting the impact of Russian disinformation.

Yet, for climate change, inoculation faces steep challenges. Decades of oil-funded campaigns have deeply ingrained skepticism and denial in the public psyche. “It’s really hard to think about someone who hasn’t been exposed to climate skepticism or disinformation from fossil fuel industries,” notes Emma Frances Bloomfield, a communication professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Bloomfield suggests that simply citing scientific consensus won’t cut it for skeptics. Their doubts stem from a deeper distrust in scientific authority and are tied more to personal values than to facts. Furthermore, the narrative of climate change often paints us as the villains, responsible for environmental degradation, and demands significant sacrifices – a bitter pill to swallow for many.

Fighting climate disinformation is an uphill battle.

The purveyors of doubt – fossil fuel companies, trolls, and geopolitical adversaries – find it easy and cost-effective to spread skepticism. In contrast, establishing irrefutable scientific truth requires a Herculean effort. It’s no wonder then that Shell, ExxonMobil, and BP have poured millions into politically charged Facebook ads this year alone.

One ray of hope lies in “deep canvassing,” a method pioneered by LGBTQ+ advocates. It involves empathetic, one-on-one conversations where concerns are heard, and common ground is sought.

This approach has shown promising results in various contexts, from reducing transphobia to swaying public opinion on renewable energy in a metal-smelting town in British Columbia.

In Trail, a town initially resistant to environmental initiatives, deep canvassing led to a staggering 40% shift in public opinion, culminating in a commitment to 100% renewable energy by 2050.

More To Discover

- How Solar and Battery Storage Advances Are Powering Change in Africa and 2024 Will Be Even Better

- Amphibious Electric Vehicle Engineered for a Climate-Changed World

- There Are Trillions of Tons of Clean Power Beneath U.S. Soil

- Earth’s Northern Crown At Risk: Our Largest Continuous Expanse of Wilderness Is Shrinking

Beyond deep canvassing, Bloomfield advocates for a shift in climate communication strategies, especially for conservative audiences. Instead of focusing on global systems and remote scientific authorities, she suggests honing in on local issues and familiar faces. Personal connections, after all, can be powerful conduits for changing minds.

In the end, battling climate disinformation may be less about bombarding skeptics with facts and more about engaging them in a narrative that resonates with their values and experiences. It’s a complex, nuanced endeavor, but one that’s crucial for our planet’s future.